A distinguished law graduate from Campus Law Centre, Delhi University. Read More

ABSTRACT:

Chapter XVII (Sections 138-148) of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881, establishes the legal liability for the dishonour of cheques in India. For an offence to be constituted, the specific ingredients outlined in Section 138 must be met. Critically, this offence is one of strict liability, meaning the drawer’s awareness or lack thereof regarding insufficient funds in the account is not a prerequisite for proving guilt.

During the stipulated 15-day notice period provided under section 138, if the drawer defaults on payment, then only a cause of action arises against the drawer. This procedural prerequisite was definitively clarified by the Apex Court in Yogendra Pratap Singh v. Savitri Pandey (2015 SC), affirming that complaints must be lodged strictly after the expiration of this statutory period.

Furthermore, a significant amendment in 2015 introduced Section 142(2), which revised the jurisdictional rules for these offences, now determining the appropriate court based on the type of cheque and the location of relevant bank branches. Finally, Section 144 precisely details the procedure for serving summons in such cases. The interplay of punitive measures and the underlying aim of debt recovery renders these proceedings “quasi-criminal” in nature, balancing deterrence with commercial efficacy.

INTRODUCTION:

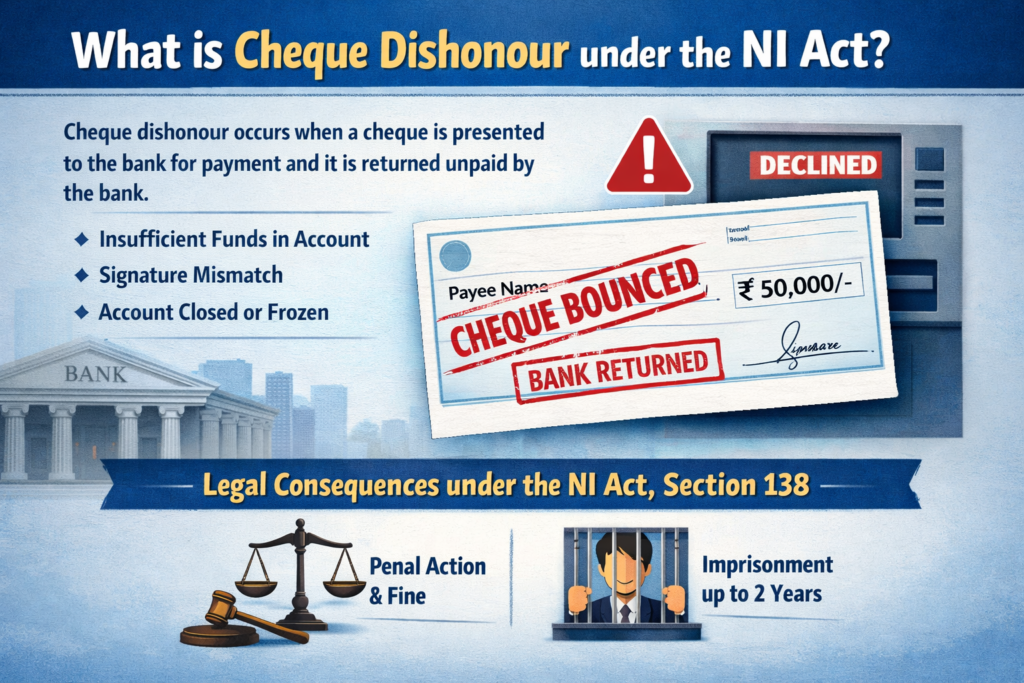

Chapter VII of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 (for brevity, NIA), titled “Penalties in case of Dishonour of certain cheques for insufficiency of funds in the accounts,” aims to ensure the trustworthiness of cheque transactions. Significant hardship arises when a cheque presented to a person is dishonoured. To deter such dishonours, the act made the dishonour of specific cheques an offence. Sections 138 to 148 of the NIA specifically address these penalties. The primary goal of incorporating this chapter is to confer confidence in cheque transactions by making cheque dishonour a punishable offence. In NEPC Micon Ltd. v. Magma Leasing Ltd. (1999 SC)[1], the Apex Court noted that Section 138 was enacted to foster faith in the effectiveness of banking transactions in commerce. Furthermore, the court observed that Section 138 effectively criminalises a contractual breach, with the legislative intent being to enhance the efficiency of banking and ensure that cheques are not dishonoured in commercial and contractual dealings, thereby maintaining credibility in cheque-based business transactions.

Understanding Cheque Dishonour under the NIA:

The Negotiable Instruments Act (NIA) outlines various provisions concerning cheque dishonour. Section 138 imposes strict liability for cheque dishonour, even if the drawer acted in good faith, if the account lacks sufficient funds or exceeds the agreed-upon overdraft limit.

Mode of Notice Under Section 138 NIA:

To constitute an offence under Section 138, the following conditions, or “ingredients,” must be met:

- a) The cheque must have been issued by the drawer to settle a legally enforceable debt or liability. Cheques given as gifts, for instance, are not covered under the NIA, as they do not arise from a legally binding obligation.

- b) Proviso (a) to Section 138 stipulates that the cheque must be presented for payment within its validity period, specifically within three months from the date it was drawn, or its period of validity, whichever comes first.

- c) Proviso (b) to Section 138 mandates that upon receiving information from the bank about the cheque’s dishonour, the payee must issue a written notice to the drawer. This notice must be:

- Issued by the payee or the holder in due course.

- In written form.

- Dispatched within thirty days of receiving the dishonour information.

- A clear demand for payment of the dishonoured cheque’s amount.

- d) Proviso (c) to Section 138 states that if the drawer fails to pay the demanded amount to the holder in due course (the complainant) within fifteen days of receiving the aforementioned notice, the offense is complete. Subsequently, the complainant has one month frooffenceate the payment was due to file a complaint.

If these conditions are satisfied and an offence is established, the penalty can include imprisonment for up to two years, a fine, or both.

The Negotiable Instruments Act (NIA) does not prescribe a specific mode for serving the notice required under Section 138. The conditions about this notice are primarily outlined in Proviso (b) and (c) to Section 138.

Crucially, judicial interpretation has established that where a notice, properly dispatched, is either returned to the sender as undelivered (for reasons such as “addressee not found,” “unclaimed,” etc.) or refused to be accepted, it can be deemed to have been duly served. This is commonly referred to as “deemed notice”.

This interpretation is rooted in the principle that courts should not adopt constructions that inadvertently benefit dishonest individuals or frustrate the legislative intent behind the Act, which aims to promote the credibility of negotiable instruments and penalize offenders for dishonor of cheques. The law seeks to penalise for evading dishonourability by simply refusing to accept or acknowledge the notice.

Section 139, read with section 118, provides a significant advantage to the holder by drawing a presumption that the cheque was issued to him in discharge of a debt or liability, though it is a rebuttable presumption. Furthermore, Section 140 prevents the drawer from claiming as a defence that they did not believe the cheque would be dishonoured when it was issued. This provision effectively removes the requirement of mens rea (guilty mind), which is usually an essential element for an offense under Section 138.

Let’s illustrate these concepts with an offence

Suppose ‘A’ (the drawer) issues a cheque to ‘B’ (the payee or holder in due course) on November 23, 2025.

- Cheque Presentation: ‘B’ can present the cheque to the bank until February 23, 2026 (within three months). If ‘B’ presents it on November 25, 2025, and it’s dishonoured with the bank sending intimation immediately:

- Notice to Drawer: ‘B’ must serve a notice to ‘A’ by December 25, 2025 (within 30 days of receiving dishonour information), as per Proviso (b) to Section 138. Let’s say the notice is served on November 27, 2025.

- Payment Window for Drawer: ‘A’ then has 15 days from November 27, 2025, to make the payment to ‘B’, which means until December 12, 2025, as per Proviso (c) to Section 138.

- Offense and Complaint Filing: If ‘A’ fails to make the payment by December 12, 2025, the offense is “made out.” ‘B’ can then file a criminal complaint.

When offencee Cause of Action Arise?

The “cause of action” for initiating proceedings under Section 138 of the NIA is triggered by Proviso (c). Specifically, if the payment demanded in the notice is not made within 15 days of its service, the right to file a criminal complaint arises. Furthermore, Section 142(1)(b) of the NIA clarifies that a complaint under Section 138 must be filed within one month from the date this cause of action accrues.

Therefore, a complete reading of Section 138, its provisos, and Section 142 NIA confirms that the cause of action accrues when the drawer of the cheque makes default in payment upon the expiry of the 15 days notice period. The offence is considered to have been commit15-dayy after this notice period expires.

In the example above, the cause of action against ‘A’ would arise on December 12, 2025. Consequently, a criminal complaint shall not be filed beyond this date, meaning between December 12, 2025, and January 12, 2026.

In M/s Saketh India Ltd. v. India Securities Ltd. (1999 SC)[2], the Supreme Court ruled that when calculating the limitation period, the date of reckoning that is the day the legal right to sue arose must be excluded. Furthermore, if the last day of this period falls on a holiday, the complaint can be filed on the court’s next working day, as per Section 4 of the Limitation Act.

Cognisance and Jurisdiction in Dishonoured Cheque Cases Under the NIA:

Section 142 of the NIA addresses two key components concerning the dishonor of cheques: cognizance of offenses and jurisdiction.

Cogni Dishonour Offences: Scognisance(1)

Seoffences2(1) outlines the process by which a magistrate takes cognisance of an offence related to a dishonoured cheque. This occurs when the magistrate, upon receiving a written complaint, applies their mind to the case to initiate proceedings as per the Act’s provisions.

Specifically, under Section 142(1)(a), cognizance is deemed to have been taken once the magistrate reviewscognisances of the complaint and subsequently issues a summons to the opposing party.

Regarding the timeline for filing a complaint, Section 142(1)(b) stipulates that a complaint is required to be filed within a month of the event that gives rise to the legal claim. If a complaint is filed beyond this one month, cognisance may only be taken if the complainant provides sufficient justification to the court for the delay.

Furthermore, Section 142(1)(c) specifies that offenses punishable under Section 138 of the NIA (dishonor of a coffenceshall be tried by either a Metropolitan Magistrate or a Judicial Magistrate First Class.

Timelines for Filing a Complaint: Judicial Precedent:

It is crucial to note the ruling in Yogendra Pratap Singh v. Savitri Pandey (2015 SC)[3]. This landmark judgment clarified that cognizance under Section 138 cannot be taken until fifteen days after the receipt of the notice issued under Proviso (c) to Section 138. Consequently, a complaint under Section 142 must be filed only after the expiry of this statutory period.

Jurisdiction in Dishonoured Cheque Cases: Section 142(2) of the NIA

Section 142(2) of the NIA, introduced by the Negotiable Instruments (Amendment) Act, 2015, specifically addresses the jurisdiction for trying offenses related to dishonored cheques. This provision includes aoffencesstanding cladishonouredg it an overriding effect over the general provisions concerning jurisdiction found in the Code of Criminal Procedure, now encompassed within the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS).

Determining Jurisdiction Under Section 142(2):

Section 142(2) of the NIA stipulates that complaints filed under Section 142(1) for offenses under Section 138 of the NIA shall be tried by a court with local jurisdiction if one of the following conditions is met:

- If the cheque is an account payee cheque, it should be processed where the payee or holder in due course holds their bank account for collection purposes.

- For cheques presented for payment through methods other than a direct account transfer, the relevant branch is where the drawer’s account is maintained.

Evolution of Jurisdictional Law: Judicial Precedent and Legislative Amendment

Prior to the 2015 amendment, the jurisdictional landscape was significantly shaped by the Supreme Court’s decision in Dasrath Rupsingh Rathod v. State of Maharashtra (2014 SC)[4] speaking for three-judge bench held that complaints concerning the, dishonor of c a heques must be filed exclusive ly in courts with authordishonour the area where the bank that holds the drawer’s account is located.

The Negotiable Instruments (Amendment) Act, 2015, effectively rendered the Dasrath Rupsingh Rathod judgment inoperative by introducing Section 142(2). This amendment shifted the jurisdictional focus. Now, the offense under Section 138 of the NIA is to be prosecuted exclusiveoffencehe court with authority over the area where the bank that holds the drawer’s account is located, specifically in cases where the cheque is intended for credit to an account.

This legislative intent was further affirmed by the Apex Court in the landmark case of Bridgestone India Pvt. Ltd. v. Inderpal Singh (2016 SC)[5]. The Court, in interpreting Section 142(2) of the NIA, clarified that for an offense under Section 138, the territorial jurisdiction to file a criminal complaint is determined by the bank branch where the payee or holder in due course has their account is considered the place where the cheque is issued for payment.

Summons Under Section 144 of the NIA:

Section 144 of the NIA outlines the procedure for the service of summons in cases where the cheque is dishonoured and resultantly, against the drawer criminal complaint has been filed. After examining pre-summoning evidence, finds a prima facie case against the accused. This section addresses three key aspects:

- Mode of Service: Section 144(1) provides that the service of summons on an accused person or a witness may be effected through speed post or other authorized courier services approved by the Sessions court. This prauthorisedms to facilitate the efficient and reliable delivery of summons.

- Place of Service: As per Section 144(1), A copy of the summons should be delivered to the accused or witness at their usual place of residence, business, or employment. This ensures that the summons is delivered to a location where the recipient is likely to receive it.

- Deemed Service of Summons: Section 144(2) deals with situations where the accused or witness refuses to accept that the summons is delivered. In such cases, upon verifying the endorsement made by an authorized person of the postal department (or approved courier sauthorisedgarding the refusal, the court may officially state that the summons has been properly delivered. This “deemed service” provision prevents individuals from evading legal process by intentionally refusing to receive a summons.

Quasi-Criminal Nature of Proceedings Under Chapter XVII of the NIA:

Chapter XVII of the NIA is often described as proceeding in a quasi-criminal manner due to the following reasons:

- Filing of a Criminal Complaint: Upon the drawer’s failure to make payment within fifteen days of receiving notice as per Proviso (c) to Section 138 empowers the aggrieved to initiate criminal proceedings against the, drawer. Such a complaint must be filed within a thirty-day window from the date the cause of action arises, which is the expiration of the aforementioned 15-day notice period. The initiation of proceedings through a criminal complaint, rather than a purely civil suit, imbues the process with a criminal character.

- Provision for Condonation of Delay: The Act also incorporates a provision for the condonation of delay in filing the criminal complaint. If the complaint is initiated beyond the prescribed thirty-day period, the court may entertain it, provided the complainant presents sufficient cause explaining the delay. This flexibility, akin to provisions found in civil procedure, allows for leniency in genuine cases of delayed filing, further highlighting the blend of criminal and civil characteristics in these proceedings.

The “quasi-criminal” designation stems from the fact that while the proceedings are initiated and prosecuted as criminal complaints leading to potential imprisonment, the underlying dispute often involves a commercial transaction and the recovery of a monetary debt, reflecting elements typically associated with civil law.

CONCLUSION:

Chapter XVII of the NIA serves to strengthen the credibility of cheque transactions and establish penal liability for default payments by the drawer. This chapter balances the interests of both parties by mandating that the drawer be given notice to make the payment. Should the drawer fail to pay before the end of 15 days of receiving such notice, a cause of action accrues, permitting the filing of a criminal complaint. Court will only take the cognizance after examining pre-summoning evidence and determining a prima facie case against the accused. The proceedings under this chapter are quasi-criminal in nature.

[1] Equivalent citations: (1999)2CALLT347(HC)

[2] Equivalent citations: AIR 1999 SUPREME COURT 1090

[3] AIR 2015 SUPREME COURT 157

[4] AIR 2014 SUPREME COURT 3519

[5] (2017) ibclaw.in 802 SC