This article has been written by Swagat Kumar Tripathy (currently pursuing a B.A LL.B at the SoA National Institute of Law, Odisha)

Introduction

Part III of the Indian Constitution encompasses the fundamental rights in it, so this is also called the Magna Carta of the Indian Constitution. All these rights ensure the liberty, equality, fraternity, and dignity of the individual, as mentioned in our preamble. The American Constitution, the Irish Constitution, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, British legal tradition, and historical documents and movements play important roles in the concept of fundamental rights. One of the fundamental rights is equality. Articles 14 to 18 contain the concept of equality. The concept of equality before the law and the concept of protective equality are laid down in this article and are regarded as the foundation of democracy and serve as pillars of justice and fairness. This article fosters a country where there is no discrimination or arbitrariness. This article is one of the basic structures of the constitution as it ensures the rule of law given by A.V. Dicey, which includes law being supreme over anything, separation of power between the different organs of the state, and understanding the legal spirit.[1]

Article 14 of the Indian constitution says that equality before the law and equal protection of the law can’t be denied by the state within the territory of India.

The negative and positive concept

In many other constitutions, the right to equality is framed in a manner similar to Article 14 of the Indian Constitution. The first part of this right, known as “equality before the law,” is generally considered a negative concept. It ensures that no individual faces discrimination. Everyone, regardless of their social status, such as a beggar or a rich person, is treated equally under the law. This principle also prevents arbitrary prohibitions, ensuring that the state remains impartial, and just, and upholds the rule of law. However, the framers of the Indian Constitution recognized that this understanding alone will not achieve true equality because different segments of society require varying levels of protection. To illustrate, consider three students in different classes: one in Class 1, another in Class 2, and the last in Class 3. If an exam were conducted based on the negative concept of equality, providing all three students with a Class 3 question paper, the intended equality would not be realized. Therefore, the framers of the Indian Constitution went beyond “equality before the law” to ensure “equal protection of the law.” This positive concept acknowledges that different groups may need different levels of legal safeguards to attain genuine equality. This comprehensive approach strives to address the diverse needs of the population while maintaining fairness and justice within the legal system.

The second part of the article says that “equal protection of law” is a positive concept as this concept does not say about equal treatment to all ignoring their inequalities. It postulates that people who are in the equal position will be treated equally. This, it supports that “there shall be equality for the equals and inequality for the unequal”.

Reasonable classification

So, equality before the law and equal protection of the law means that as two human beings are not equal in every aspect of life, the same treatment shall be given in respect of those instances where they are similar and different treatment in those aspects in which they are different. For that reason, we have to differentiate between those who are unequal and those who are equal, and that shall be based on the concept of reasonable classification. As per this concept, the legislature has the power to make laws with reasonable classification for equals to put them in one class and treat them equally. If a person wants to file a case as to violation of his right under Article 14, he has the burden to prove that he has been treated unequally among people of the same circumstances. And there is no rationale between the differentiation and the object sought to be achieved, which is called intelligible differentia.[2]

Class legislation is prohibited, but Article 14 does not prohibit the reasonable classification of a person to achieve specific objects.

For the classification to be reasonable, it must qualify two tests that are

- It should not be arbitrary or artificial.

- There shall be a reasonable nexus between the classification and the object sought to be achieved.

Union of India v. M.V. Valliappan[3] In this case, the Supreme Court observed that differentiation does not always lead to discrimination. If there is a reasonable nexus between the classification made and the object to be achieved, then it is not against Article 14.

But the Supreme Court has many times warned not to exaggerate the concept of reasonable classification because it’s a subsidiary rule evolved by the court from various cases to practically connect to the concept of equality, but overemphasis on such a concept may ruin the concept of equity, and the doctrine of classification will supersede the doctrine of equality held in the case of L.I.C. of India v. Consumer education and research center[4].

Equality- Multidimensional concept

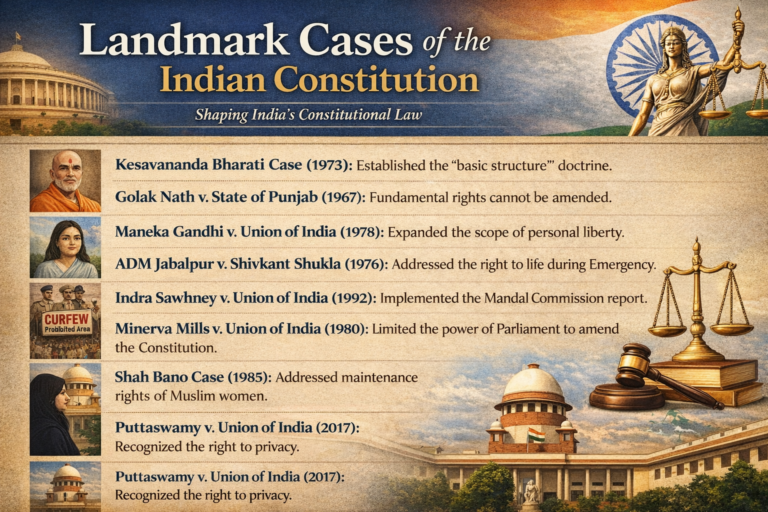

In the case of E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu[5], a new dimension of equality was pointed out, and it was said that the scope of Article 14 can’t be confined within the four walls of any doctrine as it guarantees against arbitrariness.

In Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India[6], it was said that equality and arbitrariness are inherently at odds with each other.

One-man laws

Chiranjit Lal Chowdhury v. Union of India,[7] In this case, a situation arose due to the mismanagement of the Sholapur spinning and weaving company Ltd., resulting in the scarcity of essential commodities and the laborers of the company becoming unemployed. Later on, the Sholapur Spinning and Waving Co. (Emergency Provision) Act of 1950 was passed. As per this act, the government took over the company. A person who was the shareholder of that company filed a writ in the Supreme Court for declaring the Act of 1950 void as it is against Article 14. The contention of the shareholder was that as per this act, the control and management of the company were fully taken over by the government, whereas the other companies dealing with the same were not. In this case, the court upheld the validity of the act completely and said that the company can be classified because its mismanagement results in the scarcity of essential commodities and ultimately affect the community at large. In this case, it was also emphasized that a single individual can be treated as a class.

The principles laid down are

- The constitutionality of the act should always be favored.

- If there is no reasonable classification or the classification is not proper, then the presumption can be rebutted.

- Equality of law in no way encourages the law to treat equally all people who are different by nature, birth, circumstances, etc.

- For legitimate purposes, the state can classify people.

- The classifications may result in some amount of inequality, but mere inequality is not enough.

- If a reasonable classification is made, it must be based on a real and substantial distinction, and such a classification must achieve the object.

There are instances where various laws have violated Article 14, either because there was a classification without difference or because the classification was not relevant to the object sought to be achieved.

In John Vollamattom v. Union of India,[8] Section 118 of the Indian Succession Act, 1925, restricts a Christian’s ability to bequeath his property for religious and charitable purposes. The court in this case held that the restriction imposed by Section 118 of the Indian Succession Act is unconstitutional as there is no relation between this reasonable classification made under Art. 118 and the object to be achieved. The object of this section was to prevent the transfer of property under religious consideration.

Administrative discretion

The legislature can form classes for the application of law and may leave it to the executive to make such classifications. In such cases, if any policy is mentioned in the act to exercise this discretionary power, then the act is not invalid. But if no such policy is mentioned, then the law will be declared invalid. In the Kerala Education Bill, the government is vested with the power to take over the private school. It was argued that the power vested as per this bill in the government is very wide, so it is against Article 14. The court held that general policy is mentioned in the preamble and title of the act, so the power of government can be exercised on the basis of those policies only unless it is proved that there is discrimination in implementing the policy mentioned in the preamble and title.[9]

State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar,[10] In this case, the Bengal Special Court’s Act of 1950 was invalidated because this act empowered the government to classify the crimes, classes of crimes, cases, and classes of cases as per its wish, and there were also no conditions or policies for the government to classify these acts, and the object mentioned in the preamble was for speedy trial only, which was a vague term and also uncertain for reasonable classification.

Later on, in Kedar Nath Bajoria v. Union of India,[11] the West Bengal Criminal Law (Amendment) Special Courts Act Section 4 was challenged. As per this act, the government can choose a case for reference to the special court and have it tried by special procedure. By applying this special provision, the accused will be denied certain privileges or advantages that would be provided to him if he were governed by normal procedure. The contention of the accused was that, as per the Anwar Ali Sarkar case, the act is against the constitution, so it shall be declared ultra-vires. In this case, the court rejected the contention of the accused and held that “the mentioned act clearly specifies the offenses to be tried by special courts, and the preamble also postulates that the object of the act is for speedier trial and effective punishment for the crime mentioned in the schedule.” The offenses mentioned in the schedule accurately serve the purpose of the act, and the legislation has applied its intelligible differentia in classification for the object sought to be achieved.

Conclusion

Equality, particularly protective equality, stands as the cornerstone and basis of the Indian Constitution. This constitutional provision not only ensures fairness and justice within the legal framework but also opens pathways to an inclusive and harmonious society through reasonable classification for addressing inequalities. This approach helps to foster equity within the community.

In this democratic society, citizens should advocate for a fair legal process and equal opportunities, contributing to a system where justice is not only accessible but also impartial. Moreover, educational initiatives and heightened awareness are the only solutions for citizens to become informed about their rights and to hold the authorities accountable.

[1] Constitution of England Book

[2] Western U.P. Electric Power and supply Co. Ltd v. State of Uttar Pradesh. AIR 1970 SC 21.

[3] AIR 1999 SC 2526.

[4] AIR 1995 SC 1811.

[5] 1974 AIR 555.

[6] 1978 AIR 597.

[7] 1951 AIR 1951.

[8] (2003) 6 SCC 611.

[9] 1959 1 SCR 995.

[10] AIR 1952 SC 75.

[11] AIR 1954 SCC 660.