Introduction

The Indian Criminal justice system has undergone substantial modification with the introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), which has replaced the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Legal experts and the campaigners, however, are concerned about its provisions on the protection of minorities, particularly in light of sexual abuse and discrimination. The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) lacks particular provisions designed solely for the protection of “minorities” and does not define them specifically. It does, however, have clauses that subtly protect minorities’ rights. As part of Inda’s legal reform initiatives the Indian Penal Code (IPC) is being replaced with the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), which has a number of provisions targeted at safeguarding the rights and interests of minorities. Within India’s complex and diverse society, these safeguards guarantee the protection of vulnerable groups, including linguistic, religious, ethnic, and cultural minorities.

Some relevant sections of the BNS include:

Section 153A: Offences relating to promoting enmity between different groups and inciting violence. This section prohibits speech or conduct that promotes hatred or violence against any group based on religion, race, place of birth, language, or caste1. The punishment for an offense under Section 153A can include imprisonment for up to five years and a fine.

Section 153B: The new clause criminalizes the making or publishing of false or misleading information that jeopardizes the security, unity, integrity, or sovereignty of India. The punishment for this offense is a fine, imprisonment of up to three years, or both.

Section 295A: Deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings. This section prohibits acts that are intended to insult or outrage the religious beliefs of any group2.

Section 509: Word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman. This section prohibits any act that is intended to insult.

- Prohibits promoting enmity between groups based on religion.

- Prohibits speech or acts prejudicial to national integration.

Key Changes in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita

Removal of Section 377 Provisions:

Section 377 of IPC, which had prohibited bestiality and non-consensual sexual acts, has been completely abolished by the BNS. Critics contend that by leaving out protections for LGBTQIA+ community and people who identify as masculine, these groups vulnerabilities may be exacerbated. The Supreme Court of India decriminalized consensual same-sex relations in 2018, but Section 377 still addressed bestiality and non-consensual acts.

Inconsistencies with Existing Laws:

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses Act (POCSO), which defines minors as those under the age of 18, and the BNS are reportedly at odds with one another. This concept conflicts with the BNS’s prohibitions on sexual offenses against minors, resulting in legal difficulties that may jeopardize children’s protections.

Introduction of New Offences:

The BNS keeps several of the IPC’s offenses while also adding new ones including organized crime and mob lynching. Particularly with regard to how these laws interact with currently in effect special laws, this duality may cause uncertainty in the prosecution and enforcement processes. Although the BNS introduces these new offenses, it also retains several existing offenses from the IPC.

Community Service as Punishment:

Community services is implemented by the BNS as a way to penalize minor infractions. This departure from strictly punitive methods is viewed as a more progressive and restorative approach to justice.

Key Features of Legal Safeguards For Minorities in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita:

Protection Against Hate Speech and Discrimination:

Actions that incite animosity between various groups on the basis of religious, race, caste, language, or regional identity are strictly prohibited by the BNS. To stop social unrest and persecution, offenses like hate speech, intercommunal violence, and the dissemination of false information about minorities are addressed.

Protection of Religious and cultural Rights:

The BNS guarantees that no one is subjected to discrimination on the basis of their cultural or religious identity, acknowledging India’s heterogeneous fabric. It offers defense against crimes such as forced conversion, assaults on houses of worship, and interference with religious rituals.

Safeguards Against Violence and Atrocities:

Acts of violence against people or communities because of their minority status are punishable by law. Crimes against vulnerable groups are punished harshly, and crimes like lynching, mob violence, and targeted hate crimes receive extra attention.

Criminalizing Acts of Discrimination:

The legal safeguards that protect minorities from social, political, and economic discrimination are still upheld by the BNS. It guarantees that organizations and people are held responsible for actions that marginalize or separate minority groups in different spheres of society.

Rights to Fair Investigation and Trial:

The legal system places a strong emphasis on the necessity of due process and equitable treatment for minorities. To guarantees that minorities have equal access to justice, special measures are in place to prevent bias in investigations and trials.

Protection of Minority Women:

The BNS incorporates particular protections for women from minority communities in recognition of the intersectional difficulties minority women experience. An intersectional strategy is used to combat crimes including trafficking, sexual assault, and domestic abuse, taking into account both gender and minority status.

Case Laws

- State of Karnataka v. Dr. Praveen Bhai Thogadia (2004)

• Facts: Dr. Praveen Bhai Thogadia, a leader of a religious group, was accused of making inflammatory speeches that could incite communal violence. This case addressed the issue of hate speech that could disturb public peace and incite enmity between different communities.

• Judgment: The Supreme Court held that free speech does not include the right to incite violence or create communal disharmony. The Court emphasized that speech promoting hatred against any community is not protected under the Constitution.

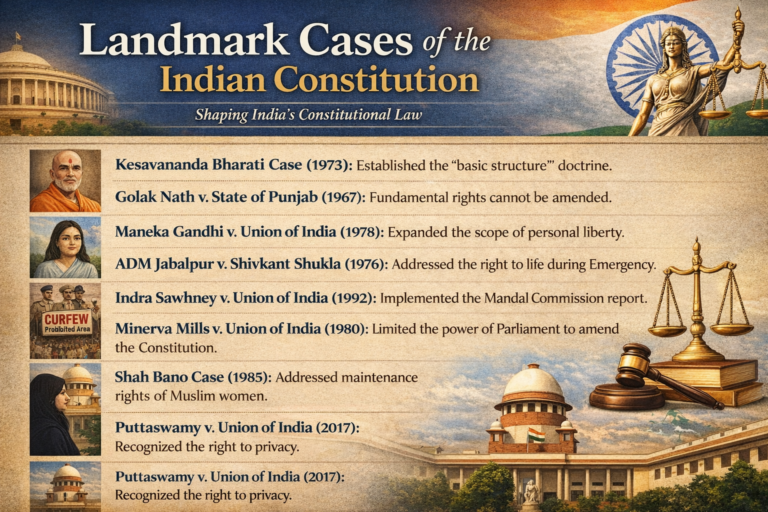

• Relevance to BNS: Provisions in the BNS like Section 153A (promoting enmity between groups) and Section 295A (outraging religious feelings) serve to protect minorities from hate speech and communal violence. This case reinforces the principle that freedom of expression must not be misused to target or harm minority groups. - Shah Bano Case (Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum, 1985)

• Facts: Shah Bano, a Muslim woman, was divorced by her husband and sought maintenance under Section 125 of the IPC. The husband argued that under Muslim personal law, he had no further financial obligations after providing a one-time settlement (mehr).

• Judgment: The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Shah Bano, stating that the right to maintenance under Section 125 applies to all citizens regardless of religion. The Court held that personal laws could not override the constitutional rights of minorities.

• Relevance to BNS: This case highlights the need for uniform legal protections, irrespective of personal law. BNS provisions related to maintenance and the protection of women’s rights continue to safeguard minority women from neglect or exploitation, consistent with the principles in Shah Bano. - Nandini Sundar v. State of Chhattisgarh (2011)

• Facts: The case was filed against the deployment of vigilante groups (Salwa Judum) in Chhattisgarh, which disproportionately affected tribal communities (a minority group). These groups were allegedly committing atrocities against tribals in the name of combating Maoist insurgency.

• Judgment: The Supreme Court held that the use of vigilante groups to fight internal security issues was unconstitutional. It emphasized the need to protect the rights of tribal minorities, who are often marginalized and disproportionately affected by such measures.

• Relevance to BNS: The BNS includes provisions to address organized crime and violence, which could encompass vigilante actions like those seen in the Salwa Judum case. This case underlines the necessity of legal safeguards to protect minority communities, particularly tribals, from state or non-state violence.

Conclusion

A major step towards updating India’s criminal law system, the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) tackles current problems like organized crime and mob lynching. But the elimination of important clauses, like those found in Section 377, raises questions about how oppressed groups—especially the LGBTQIA+ community—will be protected. Furthermore, contradictions with current legislation, such as the POCSO Act, may result in legal problems, particularly with regard to minor protection. Although community service as a type of punishment offers a rehabilitative approach, its application may be unclear, which could result in conflicting court decisions. To preserve the integrity and equity of the judicial system going forward, it will be imperative to make sure that these holes are filled.