This article has been written by Hari sri vidya Lalithambica, a law student from Padala Rama Reddi Law College.

Abstract

This article examines the recent shift in India’s legal approach toward criminal negligence following the enactment of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS), which replaces the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The focus is on Section 106 of the BNS, which expands upon the earlier framework provided by Section 304A of the IPC, refining the elements required to establish criminal negligence. This updated provision emphasizes gross negligence and a direct causal link between the negligent act and the resulting death. Judicial precedents, such as Jacob Mathew v. State of Punjab, are discussed to highlight the judiciary’s role in balancing professional accountability with fairness to individuals. Through an exploration of key cases, defenses, and practical challenges, this article demonstrates how criminal negligence law in India promotes public safety while safeguarding individuals from being prosecuted for mere errors in judgment.

Introduction

Criminal negligence plays a crucial role in maintaining public safety by holding individuals accountable for reckless conduct that endangers life. With the introduction of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS), India’s penal code framework has undergone notable changes. Section 106 of the BNS replaces Section 304A of the IPC, expanding the definition of negligence to include not only careless acts but also those that show reckless disregard for human safety. This shift underscores the law’s goal of aligning with modern legal standards, focusing on elements like duty of care, breach of duty, and criminal intent to distinguish between criminal negligence and ordinary negligence.

One significant change introduced by Section 106 is the focus on specific professional negligence, particularly in medical treatment and reckless driving. For example, doctors now face different penalties when negligence occurs during medical procedures, reflecting the need to balance accountability with professional autonomy.

This article delves into the elements required to establish criminal negligence, examines judicial precedents that have shaped this area of law, and explores the defenses available to those accused. It also discusses the broader societal and professional implications of these laws. By evaluating how the new legal framework fosters public safety while addressing individual liability, the study provides insights into the challenges and future direction of criminal negligence law in India.

Legal Framework of Criminal Negligence in India

Section 106 of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (hereinafter referred to as BNS) addresses the offence of “causing death by negligence”.

“(1) Whoever causes the death of any person by doing any rash or negligent act not amounting to culpable homicide shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to five years, and shall also be liable to fine; and if such act is done by a registered medical practitioner while performing a medical procedure, he shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, and shall also be liable to fine.

Explanation: For the purposes of this sub-section, “registered medical practitioner” means a medical practitioner who possesses any medical qualification recognized under the National Medical Commission Act, 2019 (30 of 2019) and whose name has been entered in the National Medical Register or a State Medical Register under that Act.

(2) Whoever causes the death of any person by rash and negligent driving of a vehicle not amounting to culpable homicide, and escapes without reporting it to a police officer or a Magistrate soon after the incident, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine”.

The Section 106 of BNS, 2023 brings several important changes compared to the older section 304A of the IPC, 1860. The scope of the definition under section 106 expands to include not only careless acts but also those that show reckless disregard for human safety.

The IPC provision treated all negligence equally, including that of medical professionals. Doctors could face up to two years of imprisonment for negligent conduct, without any differentiation. In contrast, section 106 of the BNS introduces special provisions for medical practitioners. If a negligent act occurs during a medical procedure, the penalty is limited to two years imprisonment and a fine. This ensures accountability without discouraging medical professionals from performing high-risk procedures.

Section 304A did not explicitly address hit and run cases. Road accidents caused by the reckless driving were treated same as other negligent acts, however, section 106 introduced a specific provision whereby if the driver causes death because of rash and negligent driving and escapes without reporting such incident to a police officer or a magistrate shall be punished with up to ten years of imprisonment. The introduction of stricter punishments and the requirement to report the accident to either a policer officer or a magistrate deters reckless driving, encourages timely reporting and accountability, and builds trust in the legal system.

Section 106 provides for clearer guidance by stating that negligence must reflect reckless disregard for life and safety. This clarity helps courts more effectively distinguish civil negligence from criminal negligence, unlike section 304A.

To constitute an offence under section 106 of BNS, the following essential ingredients need to be satisfied.

- Death of an individual

The first essential ingredient is that the act or omission results in the death of an individual. Negligence reflects reckless disregard for life or a failure to exercise the care expected in that situation.

- Death was the result of a negligent act by the accused

Negligence must be a direct cause of the victim’s death, even if the act was not committed with any intention to harm. Rash or careless behavior, such as reckless driving or failure to act prudently in medical treatment, can amount to negligence.

- The act does not amount to culpable homicide

Criminal negligence under section 304A involves an unintentional act or omission leading to death, whereas culpable homicide under section 299 the intention to cause death or knowledge that the act is likely to cause death.

If the intention or knowledge element is missing, the case will fall under Criminal negligence, i.e., under section 304A of Indian Penal Code

- Mens rea

Although criminal negligence is generally associated with lack of intent to harm, the law still requires a minimum degree of recklessness or disregard for life and safety to constitute the offence. In cases of criminal negligence, the accused’s act should reflect gross negligence or recklessness, going beyond simple carelessness.

The courts have held that not every negligent act attracts criminal liability unless it exhibits a substantial degree of carelessness.

Jacob Mathew vs State of Punjab[1]

Supreme Court of India laid down crucial guidelines for determining criminal liability of medical professionals. The Court emphasized that criminal negligence requires gross negligence or recklessness that goes beyond ordinary mistakes. It held that an ordinary error in judgment or an accident during medical treatment would not amount to criminal negligence unless the doctor’s actions were so reckless that they endangered the patient’s life.

The judgment aimed to protect medical professionals from undue criminal liability while ensuring accountability in cases of gross negligence. It also established that simple negligence might attract civil liability, but only gross negligence or extreme recklessness should lead to criminal prosecution.

N. Hussain vs State of Andhra Pradesh[2]

The Court clarified that some degree of awareness of the risks involved in the act is necessary for it to qualify as criminal negligence. In the absence of intent to harm, the negligence must be so significant that it reflects a conscious disregard for the safety or well-being of others.

The accused must owe a duty to act prudently towards the victim or the public. A legal duty exists when the accused’s actions create a foreseeable risk of harm to others. There must also be a clear failure to fulfill the duty of care owed to the victim. A breach indicates that the accused did not act as a reasonable person would have in similar circumstances. Moreover, the negligence must directly result in harm or damage, establishing a causal link between the accused’s negligent act and the resultant death. While the act should not be intended to harm, it must exhibit a degree of recklessness or disregard for consequences that would make the act criminally negligent.

Defenses Available for Criminal Negligence

In cases of criminal negligence under Section 106 of BNS, the accused can raise several defenses to avoid liability. These defenses aim to show that the act did not involve gross negligence or recklessness, or that the accused had no reasonable control over the outcome.

- Absence of Causal Link

- No Gross Negligence or Recklessness

- Act of God or Unforeseeable Events

- Voluntary Consent or Assumption of Risk

- Contributory Negligence by the Victim

- Emergency Situations or Necessity

- Lack of Mens Rea (Guilty Mind)

Judicial Interpretations

The Indian judiciary has played a crucial role in interpreting the scope and nature of criminal negligence under Section 304A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860. Courts have emphasized that criminal negligence involves gross negligence or reckless disregard for life, distinguishing it from ordinary carelessness that results in civil liability.

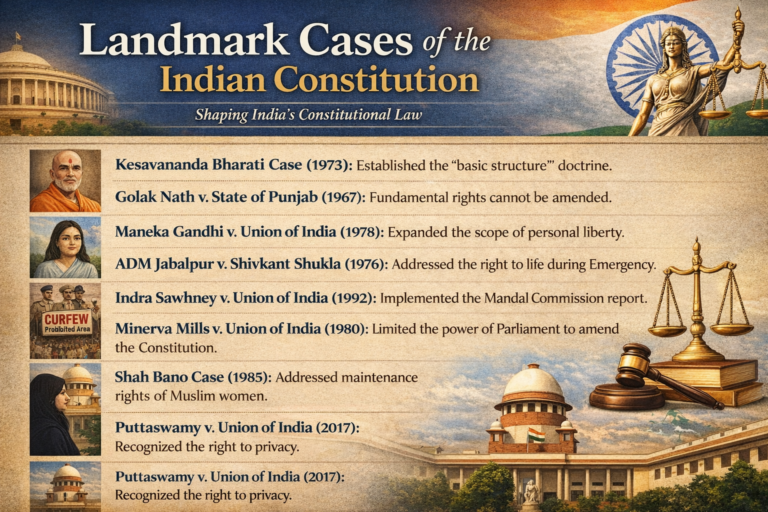

- Kurukshetra University v. State of Haryana

This case reiterated the principle that death must be a direct result of the negligent act for the offense to fall under Section 304A IPC. The Court emphasized the importance of proving a causal link between the accused’s act and the death of the victim, ruling that incidental or coincidental factors are insufficient to attract criminal liability.

- Malay Kumar Ganguly v. Dr. Sukumar Mukherjee & Ors[3]

The case is a landmark judgment on medical negligence in India, it arose from the death of Anuradha Saha due to alleged improper treatment by Dr. Sukumar Mukherjee and others. The Supreme Court reiterated that criminal liability for medical negligence requires gross negligence or recklessness, following the principle laid down in Jacob Mathew v. State of Punjab (2005), while ordinary negligence only attracts civil liability. Although the doctors were not held criminally liable, the Court awarded Rs. 5.96 crore in compensation, one of the highest in Indian medical negligence cases, reflecting the need for accountability in healthcare. The judgment emphasized balancing patient rights and doctor protection, ensuring professionals are not prosecuted for minor errors but are still held responsible for grave negligence.

- M/s. Spring Meadows Hospital & Anr v. Harjol Ahluwalia through K.S. Ahluwalia & Anr. [4]

This case involved a case of medical negligence where a young boy, admitted for treatment of typhoid, suffered brain damage after being administered a wrong injection by a nurse. The Supreme Court ruled that both the hospital and the attending doctors were liable, emphasizing the duty of care owed by hospitals and healthcare providers to both patients and their guardians. The judgment also recognized the consumer rights of patients under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986, establishing that patients can seek compensation for medical negligence not only for themselves but also on behalf of dependents.

- Rathnashalvan v. State of Karnataka (2007)[5]

This case reinforced the distinction between culpable homicide (Section 299 IPC) and criminal negligence (Section 304A IPC). The Court ruled that Section 304A applies only when there is no intention or knowledge that the act would result in death. If the accused had intent or knowledge, the act would amount to culpable homicide or murder.

- Kusum Sharma & Ors. v. Batra Hospital & Medical Research Centre & Ors. (2010) 3 SCC 480

In this judgment, the Supreme Court provided clarity on medical negligence and the standard of care required from healthcare professionals. The Court ruled that negligence cannot be presumed solely because a patient suffers a poor outcome. The doctor’s conduct must be evaluated in light of the circumstances at the time of treatment, applying the Bolam test—which asks whether a responsible body of professionals would have acted in the same way. It was emphasized that only gross negligence or reckless disregard for a patient’s safety would attract criminal liability under Section 304A IPC.

- Ravi Kapur v. State of Rajasthan[6]

This case addressed criminal negligence in the context of reckless driving. The accused was charged under Section 304A IPC after causing a fatal road accident due to negligent driving. The Supreme Court observed that negligence in driving must not only be established but should amount to rashness or recklessness, creating a significant risk to life. The judgment emphasized that careless driving, especially when it disregards traffic rules and public safety, warrants strict criminal liability under Section 304A, as such actions reflect gross negligence resulting in loss of life.

Consequence of Criminal Negligence

The consequences of criminal negligence under Indian law extend beyond mere legal penalties. Individuals found guilty of such offenses often face personal, professional, and social repercussions.

- Imprisonment and Fines: Depending on the severity of the negligence, offenders can face imprisonment ranging from a few months to several years. Fines may also be imposed, especially under Sections 304A and 338.

- Social Stigma and Loss of Reputation: Offenders may suffer from social alienation and loss of reputation. Medical practitioners, for instance, might lose their license if found guilty of criminal negligence.

- Civil Liabilities: Although criminal negligence attracts penalties under criminal law, offenders may also face civil lawsuits for compensation by the victims or their families.

- Impact on Employment and Professional Licenses: Professionals such as doctors, engineers, or drivers may lose their right to practice or be suspended from employment if their negligence results in criminal charges.

One of the challenges in criminal negligence cases is distinguishing them from civil negligence. The difference lies primarily in the degree of carelessness involved. While civil negligence cases aim to compensate victims through monetary relief, criminal negligence is prosecuted to maintain public order and prevent dangerous conduct. Courts often grapple with whether an individual’s actions are careless enough to warrant criminal prosecution.

Medical negligence cases, in particular, highlight this thin line. Not every medical complication is treated as criminal negligence, as recognized in Jacob Mathew’s case. Only cases where doctors exhibit an extraordinary lack of care—such as abandoning a critical patient without reason—are treated as criminal acts.

Challenges in Enforcement and Interpretation

The enforcement and interpretation of criminal negligence in India face significant challenges. How can the legal system effectively navigate the ambiguity in defining “gross negligence” when such uncertainty leaves room for inconsistent rulings? Courts often interpret it on a case-by-case basis, leading to a lack of clarity in legal standards. Distinguishing civil from criminal negligence presents another hurdle, particularly in complex areas like medical malpractice and road accidents. In situations where recklessness must be proven beyond mere carelessness, how can we ensure that the threshold for liability is appropriately set? Delays in investigation and trial further complicate the process, weakening evidence over time and potentially undermining justice. In a landscape where public opinion and media pressure can skew the enforcement of justice, how do we maintain impartiality? Additionally, evolving technologies and changing professional standards make it increasingly difficult to establish consistent benchmarks for liability. These challenges, combined with the high burden of proof required in criminal cases, often make securing convictions a formidable task. As we consider these complexities, how can we reform the legal framework to better address the nuances of criminal negligence?

Conclusion

The enforcement and interpretation of criminal negligence laws in India face challenges such as ambiguity in defining gross negligence, distinguishing civil from criminal negligence, trial delays, and media influence. To address these issues, several legal reforms are essential.

First, clear statutory definitions and sector-specific guidelines will reduce inconsistencies in court rulings. Establishing fast-track courts will help minimize delays and ensure timely justice, while AI-based evidence management and mandatory accident reporting systems can improve investigative efficiency and accountability.

To safeguard impartiality, judicial processes must be protected from media pressure, and judges should receive training on evolving professional standards. Additionally, adopting reformative measures—like community service or safety training—alongside punitive actions can promote behavioral change.

With these reforms, the legal framework will become more consistent, efficient, and just, ensuring that criminal negligence laws balance accountability with fairness, while fostering public safety and trust.

[1] AIR 2005 SUPREME COURT 3180

[2] AIR 1972 SC 685

[3] AIR 2010 SUPREME COURT 1162

[4] 4 SCC 39

[5] AIR 2007 SUPREME COURT 1064

[6] 9 SCC 284