India’s Sandal Scandal

ABSTRACT

In an increasingly globalised fashion industry, the thin line between appropriation and inspiration has become a contested ethical and legal issue. This paper examines the recent controversy surrounding the luxury fashion brand Prada, and its apparent appropriation of the traditional Indian Kolhapuri Chappals, a product with a geographical Indication (GI). It rekindled discussions about surrounding cultural appropriation as well as the inadequacy of current intellectual Property protections and most importantly, the exploitation of indigenous craftsmanship by international brands, all by showcasing a scandal design strikingly similar to the Kolhapuri chappals without attribution or any acknowledgment. This paper essentially delves into the legal framework that governs Geographical Indication protection in India, juxtaposed with certain international IP regimes, in order to assess whether artisans and cultural communities possess adequate mechanisms to assert their rights in cross-border disputes. It also evaluates the broader implications on ethical fashion and cultural heritage preservation, and the responsibilities of multinational corporations. Ultimately, it underscored how critical it is to close the essential gap between Intellectual Property Law and cultural rights by promoting stricter enforcement, acknowledgement and respect for traditional knowledge in global marketplace.

Keywords: Fashion Industry, Cultural Appropriation, Geographical Indication, Intellectual Property, Cross-Border disputes

INTRODUCTION

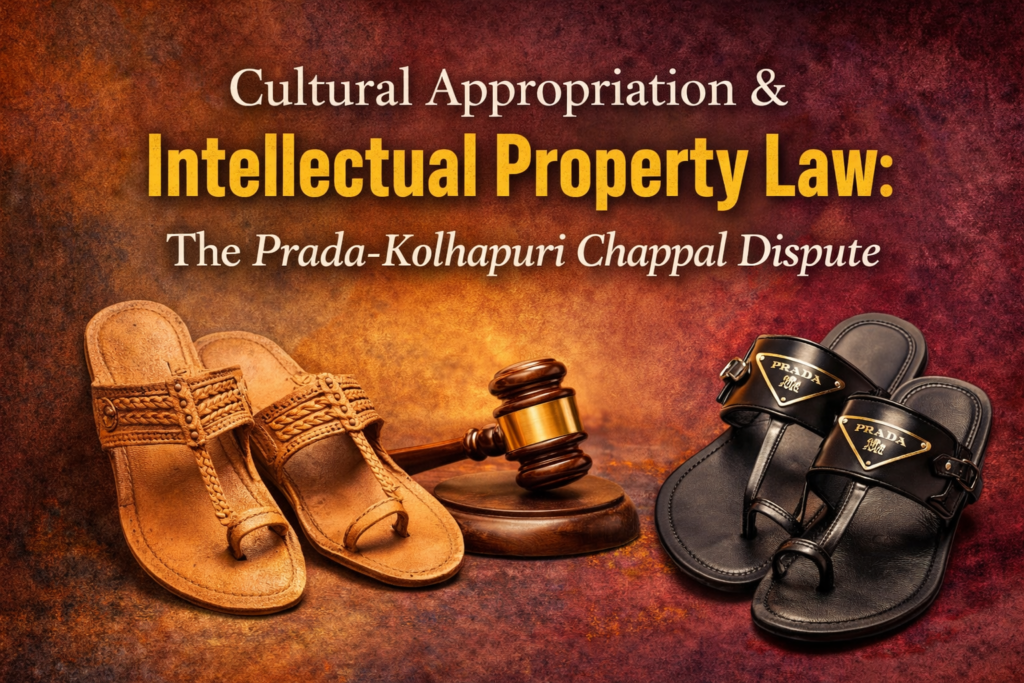

A powerful global fashion brand is in the talks. And this time it’s not about style, but stolen identity. In the month of June, 2025, the Italian luxury fashion house Prada unveiled its Spring/Summer 2026 menswear collection. It featured open-toe leather sandals and leather toe-ring invite cards that bore a striking resemblance to the traditional Kolhapuri Chappals, giving it a western spin, which were reportedly priced around Rs, 60,000 to Rs 1.17 Lakh or over 1,000 Euros. Kolhapuri chappals are considered as centuries old handcrafted footwear originating from Maharashtra, India. Prada failed to mention the sandals’ cultural or geographical origins, nor did it give any recognition or credit to the Kolhapruti artisans who have been preserving this craft through generations. This expensively priced sandals caused a great deal of indignation and outrage in India and revealed not only the deep-seated issue of cultural appropriation but also the limitations of current legal frameworks in protecting indigenous art forms on the global stage.[1]

It underscores the recurrent imbalance between strong multinational corporations as well as the economically vulnerable artisan communities. While India’s Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999, provides protection for Kolhapuri Chappals, the effectiveness of such protection against foreign appropriation remains questionable. Despite being registered and represented by GI associations, the artisans were left with little to no recourse. This raises a critical issue: Has the GI Act fallen short of safeguarding the legitimate interests of Indian stakeholders, or is its application to dealing with cross-border violations inevitably constrained?

ANALYSIS

As we all know, the recent global spotlight on the heritage of India in the fashion industry reveals a nuanced dynamic between cultural appreciation as well as cultural appropriation. Let’s start with the good bit. Louis Vuitton’s Men’s Summer collection is a good example of a cooperative and a respectful method of presenting the Indian culture. By commissioning the famous Indian architect Bijoy Jain to design a visually arresting eye-catchy ‘Snakes-and-Ladders’ themed runway, which paid homage to a game with Indian roots, the brand certainly showed that it was making an attempt to connect with the cultural story that it aimed to portray. The collection, appropriately named ‘A Voyage to India’ presented India as a major theme that was investigated through careful design, and framed our country not merely as an aesthetic inspiration, but as a central theme explored through thoughtful design.

This incident contrasts sharply with Prada’s contentious introduction of footwear inspired by Kolhapuri Chappals that was made without recognition or credit. Prada’s strategy was certainly characterised by omission and contempt, in contrast to Louis Vuitton’s choice of inclusivity and respect. While the latter commodifies Indian culture for profit without giving it the credit it deserves, the former honours it through smart alliances as well as respectful representation.

This diversion highlights a crucial difference in fashion’s engagement with cultural elements i.e. between appreciation, which uplifts and collaborates with source communities and appropriation, which extracts and exploits. Lack of credit reflects branding over craftsmanship, which is the mindset globally.[2] While Prada has tried to make amends, it is not the first time a big fashion brand has used a local artisan’s ideas. It is imperative to note that for artisans, it is a matter of survival first, and then a matter of pride, hence they need to be moved above the stage of survival.

Kolhapuri chappals are open leather sandals known for their distinct leather strap and toe hold. They have to be crafted by bare hands. This craft has passed down since centuries and nearly a 100,000 artisans make Kolhapuri chappals around India. Many of them come from marginalised communities and face low wages soaring material costs and tough working conditions. This kind of cultural appropriation happens far too often with no real collaboration. The India Chikankari for instance. From mirror works to fancy embroidery and cloth printing techniques, traditional designers have frequently inspired global runways, but the artisans behind them often remain invisible, while the brands profit from it.[3] Artisans tend to earn a fraction despite their skill, their talent. Beyond legal protection, it is also about ethical recognition.

It is both feasible and essential for India to raise and bring up the subject of GI enforcement in foreign jurisdictions at a government-to-government level, particularly for goods that are ingrained in the country’s rich cultural and civilisational legacy. Kolhapuri chappals are more than simply shoes, it represents centuries of traditional wisdom and excellent craftsmanship. There are examples that show the possibility of effective government action, such as APEDA’s (Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority) proactive role in safeguarding GI-tagged Basmati rice. For non-agricultural GI items, which can empower traditional craftspeople, preserve legacy, and make a substantial contribution to India’s rural economy and global cultural impact if properly marketed and preserved, a similarly targeted strategy is necessary.

Where Law meets Fashion

Geographical Indication or GI is a form of intellectual property that was introduced in India in 1999. It identifies goods as originating from a specific region, locality or country. It is linked to having a specific geographical origin, with a particular quality, reputation and characteristics which essentially attributes to that place of origin. In addition to preserving cultural and traditional knowledge, this acknowledgment ensures that profits from these goods flow back to the communities that have supported and nurtured them for generations. At present, there are 658 registered GI-tagged products in India that represent diverse sectors ranging from handicrafts and textiles to agricultural and food items, each reflecting the rich cultural heritage of their respective regions. For example, Kancheepuram Silk Sarees from Tamil Nadu (Southern India), Pashmina (Jammu & Kashmir), Mysore Sandals (West), and many more. GI essentially protects the right of those artisans who have been carrying out such art from generation to generations. It protects the identity as well as the authenticity.[4]

Legal action in cases of cultural appropriation is essential for maintaining traditional knowledge and fostering rural economic development, and it goes beyond simply demanding compensation for violation. By giving traditional goods uniqueness and authenticity through systems like Geographical Indications (GI), artisan groups are empowered economically and their legacy and skills are not only preserved but also profitably exploited. In 2019, for example, Kolhapuri chappals were granted GI protection in order to preserve the interests of Karnataka and Maharashtra craftspeople.[5] The entire goal of GI protection was compromised by Prada’s unapproved use of this design without acknowledgement or payment, which also hurt the rural stakeholders’ ability to make money.

Can Indian GI laws be enforced against foreign entities like Prada?

International Legal frameworks hold the solution. India stands as the member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and a signatory to the TRIPS Agreement (Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights), which requires member governments to mutually respect and safeguard each other’s Intellectual Property Rights. Legal accountability across national borders is made possible by the worldwide duty under TRIPS to acknowledge and uphold GI safeguards. The legal basis for holding foreign businesses accountable is in place, even though real enforcement is still difficult, especially for populations that are economically disadvantaged. In industries like agriculture, crafts, and fashion, where respect for intellectual property is critical to international trade and development, upholding such rights is crucial for both justice and the development of moral, sustainable business practices.

The TRIPS Agreement (administered in part by WIPO) specifically contains provisions for the preservation of geographical indications. While it offers enhanced protection for wines and spirits, the traditional handicrafts like the Kolhapuri chappals are not really given or afforded the same level of international safeguarding. Because of this discrepancy, such culturally significant products are often susceptible to appropriation in global marketplaces. Nevertheless, the Indian government has diplomatic and legal avenues for improving GI protection abroad. This includes using trade agreements for negotiating better recognition and enforcement of Indian GIs, engaging WIPO mechanisms, signing bilateral or multilateral agreements and starting mediation or arbitration procedures.

What should be done?

A significant challenge in protecting traditional crafts like Kolhapuri chappals lies in the unorganised nature of the artisan communities. Many of them lack formal legal representation, any institutional support, and most importantly, awareness of their intellectual property rights. While the GI registration acts as a legal shield, its effectiveness is proportional to its active enforcement, which requires coordination, knowledge as well as access to legal resources. As for most artisans, immediate economic survival comes before pursuing legal claims, making it challenging to prioritize action against infringement. Due to this lack of proactive enforcement and lack of legal awareness, the foreign entities tend to exploit traditional designs with little to no fear of its consequences.[6]

Filing a legal action in cases of cultural appropriation is imperative for preserving traditional knowledge and fostering rural economic development, as it goes beyond merely seeking compensation for infringement. By granting traditional goods exclusivity and authenticity through systems like Geographical Indications (GI), artisan communities are empowered economically and their heritage and skills are not only preserved but also commercially rewarded. In 2019, for example, Kolhapuri chappals received GI protection in order to preserve the interests of artisans in Karnataka and Maharashtra. Meanwhile Prada’s unauthorised use of this design without credit or compensation undermined the very purpose of this protection.

CONCLUSION

A model of cooperation based on respect for cultural heritage might be fostered after the ongoing discussions between Prada and the Maharashtra Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (MACCIA), which could set a crucial precedent for ethical fashion. If this becomes successful, this interaction could help open doors and pave way for international fashion brands to respect the heritage of the designs and thereby honouring the legacy behind the designs they draw inspiration from.

The constant challenges faced by the Indian artisans in protecting their traditional crafts against global appropriation becomes the main highlight of the Prada-Kolhapuri controversy. Despite India’s efforts in offering a legal framework through Geographic Indication (GI) system which is intended to protect the authenticity and the monetary rights of the artisans, several limitations are revealed in the present case in terms of enforcement, especially against foreign corporations. This case undermines the livelihoods of the artisans due to inadequate credit and compensation. Further, protecting cultural heritage is not only essential for safeguarding traditional knowledge or a matter of law but also of justice and respect for the communities that have preserved these crafts for generations. Moving forward, stronger international cooperation, clearer legal mechanisms for enforcing GI rights beyond India’s borders, and increased ethical accountability from global brands are crucial. Ultimately, a balance must be struck between cultural appreciation and appropriation, since a brand like Prada is a great stage for a recognition globally, however it must be one that honours the artisans contributions, sustains economic welfare and preserves the integrity of the rich legacy.

Through legal education, capacity-building programs, and assistance from the government and civil society, craftsmen must be empowered to effectively defend their rights and conserve cultural heritage. By forming official groups with the help of legal professionals, local communities can keep an eye out for violations and take prompt legal action. Without this kind of group empowerment, the GI framework is underutilised and there is a continued risk of cultural appropriation, which denies craftsmen the respect and recognition their legacy merits in addition to financial gains.

[1] Sanjay Jain, Prada-Kolhapuri Chappal Controversy: Tip of the Iceberg, Bar and Bench – Indian Legal news (Jul. 26, 2025), https://www.barandbench.com/columns/prada-kolhapuri-chappal-controversy-a-tip-of-the-iceberg.

[2] Prada- Kolhapuri Controversy: Why Luxury Brands Keep Getting India Wrong, (Jul. 18, 2025), https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cgmwnlnrd1eo.

[3] How Prada-Kolhapuri Controversy Exposes the Continued Exploitation of Artisan Communities, The Indian Express (Jun. 29, 2025), https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-global/prada-kolhapuri-controversy-10094130/.

[4] Jain, supra note 1.

[5] IS PRADA GUILTY OF CULTURAL APPROPRIATION? THE KOLHAPURI CHAPPAL CONTROVERSY – J.P. Associates, (Jul. 19, 2025), https://jpassociates.co.in/prada-kolhapuri-chappal/.

[6] BBC Audio | Business Daily | What next after India’s Sandal Scandal?, https://www.bbc.com/audio/play/w3ct6rxw (last visited Aug. 3, 2025).