This article has been written by Aparajita Singh a first-year BBA LLB (Hons) student at Symbiosis Law School, Pune.

Introduction

Indian courts have received praise throughout the last few decades for upholding the fundamental rights of individuals, especially the freedom of life and personal liberty guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution. Individuals now enjoy several fundamental rights achieved in this activity, which is especially advantageous to people with low incomes and marginalised as it guarantees them the respect they are due. Nevertheless, in cases involving preventative detention statutes, judges have found it challenging to protect individual liberty notwithstanding this lobbying. In the most recent major decision about the legitimacy of post-demarcation legislation, the courts upheld the validity of the law in AK Roy v Union of India even after adding the due process clause of the constitution. Because of this, there is a contradiction between related articles of pour Indian constitution. Therefore, it is imperative to learn more about the background of Indian detention law, comprehend the rationale behind their inclusion in the constitution, and asses how the judiciary has defended these laws by limiting the reach of judicial review seventy years after the constitution was enacted. Considering all arguments against PD laws and examining their continued relevance is imperative.

Howdy, you all! Welcome to your page of knowledge. You will find different legal blogs, the latest news, current affairs, and many more on this channel. This is the initiative to develop the knowledge of the law in the world, especially for you.

What is Preventive Detention?

Our constitution defines preventative detention as detaining a person without a criminal trial. This means no charges are formally made, and no criminal offence is proven. Such detention can be carried out for reasons such as ensuring the state’s security, maintaining public order, or ensuring the availability of essential supplies and services to the community. It is important to note that according to the constitution, preventative detention laws are not required to adhere to fundamental procedural rights guarantees. These laws contrast the regular criminal justice system, which seeks to minimise custody and arrests in ordinary criminal law. A valid arrest by the police necessitates credible evidence. Pre-trial detention typically cannot be extended beyond 24 hours without meeting certain conditions.

“Preventive Detention”, as defined by our constitution, involves detailing individuals without a criminal trial, typically for investigative purposes, and is subject to periodic review. Unlike safeguards provided under ordinary criminal law, preventive detention laws allow arrest based on the subjective satisfaction of an executive officer that an individual may pose a threat to society. Grounds for arrest may not be required to be mentioned for up to 5 days. In some cases, up to 15 days after the arrest, the detainee does not necessarily have to be brought before a judge or granted access to legal representation. Advisory boards may intervene only after three months of detention, and even then, there is no legal assistance for periodic review or trial.

The primary objective of preventive detention laws is to prevent individuals from engaging in prejudicial acts against the defence security of the state foreign affairs essential supplies and services, or public order courts have held that such laws are preventative rather than punitive measures based on the subjective satisfaction of administrative authorities

The Constitution provides specific grounds for detention under statutes including the security of india foreign affairs defence mainatanvvce of supplies and essential services and maintenance of public orders.

Detainees under these laws are not entitled to the right guaranteed under article 19 or 21, certain safeguards are provided to detainees under these laws, including a maximum detention period of three months, approval of the advisory board if detention exceeds this period, communication of grounds for detention to the detainee, and an opportunity for the detainee to make representations before the detaining authorities. However, these safeguards do not apply to enemy aliens.

Detainees can challenge detention orders through writ proceedings with judicial interference limited to specific circumstances.

The History and Evolution of Laws Surrounding Preventive Detention in India

It dates back to the colonial era under British rule. As early as the 19th century, a regulatory framework existed allowing British authorities to arrest and detain individuals without trial and detainees being denied the writ of habeas corpus. Emergency legislation during World War II and I, such as the Defence of the Realm Act and the Defence of india act, authorised preventative detention to safeguard national security. Preventive detention measures from peacetime, such as the Rowlatt Act and the Bengal Criminal Law Amendment Ordinance, replaced these regulations from the war era.

To give the government the authority to hold anyone who is seen to pose a threat to public order, national security, or vital supplies and services, the Defence of India Act and regulations were passed after World War II.

Article 22 of the constitution lays out the rules about preventative detention.

Amid a discussion about whether due process of law or procedure established by law should be included in article 21 article 22, which was once known as a draft of article 15. After debates between Justice Frankfurt and dir BN Rau, the official constitutional advisor, the concept of due process of law was eventually dropped from Article 15, and the phrase procedure established by law was selected instead.

The Constituent Assembly adopted Rau’s request to substitute the procedure established by law for the phrase due process of law in draft Article 15.

It was also the intention of the framers of the Constitution to support preventative detention legislation by substituting procedures established by law for due process of law.

Dr BR Ambedkar introduced Article 15 A in the assembly after expressing his displeasure with this modification. This drafting committee suggested this article to make up for Article 15 omission and to protect each person’s right to personal liberty because Dr. Ambedkar anticipated that the executive and legislative branches would misuse their authority to hold people without following the law, Article 15 A was introduced to give certain procedural rights in the circumstances involving preventative detention. Despite this, Article 15 A was stricken with a proviso that said its rights did not apply to cases of preventative detention.

Instead of stifling Article 21, Article 22 was implemented to enhance it. Historian Granville Austin explained how preventative detention laws are entwined with the constitutional framework link between liberty and due process. It was provided to the parliament to define circumstances in which the advisory board’s consent was not needed for detentions longer than three months and to establish guidelines for the advisory board during the detention procedure.

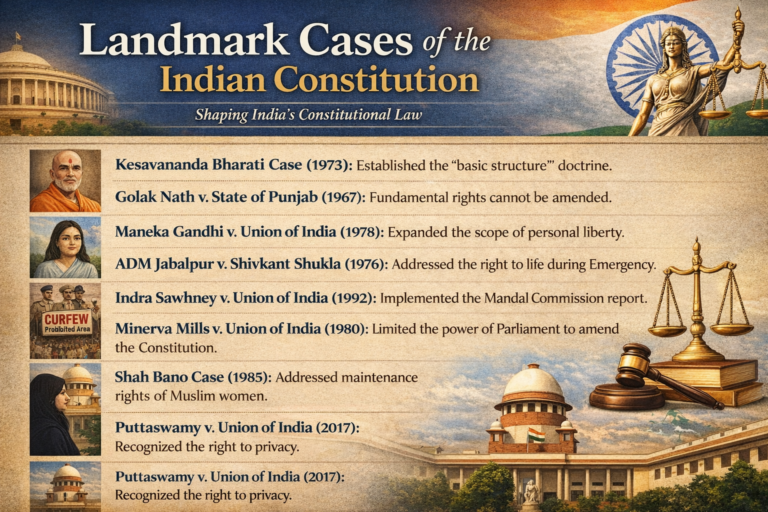

The Supreme Court heard challenges to the Preventive Detention Act 1950 brought for by the communist leader AK Gopalan, who claimed that articles 14,19,21 and 22 had been violated in the historic case of AK Gopalan v. State of Madras. The court upheld Article 22 coexistence with Article 21 and rejected the claim that it formed a complete code; however, the court misinterpreted Justice Mahajan’s minority decision in the Gopalan case in a later instance, holding that 22 was established as a complete code

The complete code argument in the Gpalan case was found to be unworkable in other instances, such as RC Cooper, which determined that preventive detention regulations must adhere to the legally mandated provisions of Article 19 without changing the wording of Article 21.

Preventive detention laws are enacted by the Parliament and state legislatures, respectively, introducing the notion of “just, fair, and reasonable” treatment into the interpretation of Article 21 of the Union List and Entry 3 in the Concurrent List.

This was made possible by the Francis Coralie Mullin case. The Supreme Court has stated that laws about preventative detention do not necessarily need to address specific defence or foreign policy issues.

The Indian government initially passed the Preventative Detention Act in 1950, which permitted the arrest and detention of people without charge or trial for maintaining public safety and security; the Gopalan case affirmed the legality of this act except for some section 14 provisions, which were declared invalid because they did not comply with article 22 complete list of conditions.

Acted in 1969, the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) shared several sections with the Preventive Detention Act. It was heavily utilised as a political tool when the emergency was declared in the middle of the 1970s. After MISA expired in 1978, the National Security Act (NSA), which is still in effect, was quickly passed. Those judged detrimental to certain facets of public order and national security may be detained in anticipation of their arrest under the NSA.

The Supreme Court affirmed the legitimacy of the National Security Agency (NSA) in the case of AK Roy v. Union of India, primarily because the NSA’s goals corresponded with those listed in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. Even if Article 21 was expanded to include the right to counsel in Maneka Gandhi’s case, the Act’s provision denying that right was upheld. The Defence of India Act and Defence of India Rules were passed during the 1962 Sino-Indian War, giving the federal and state governments the authority to imprison people whose actions are judged to be harmful to the country’s defence, civil defence, public safety, public order, foreign relations, peaceful conditions, military operations, or vital supplies and services.

Although preventative detention is covered by Rule 152 of these regulations, it has never been used. The Supreme Court has emphasised the importance of strictly adhering to the preventive detention provisions under these rules. It has made it clear that only a district magistrate or another competent authority may issue a detention order, with other district magistrates serving in an additional capacity as district magistrates not being eligible.

The authority responsible for detaining an individual must inform them of the reason for their imprisonment. This is crucial to guarantee that the detainees can defend themselves and obtain adequate legal representation. Failure to provide such information is deemed an unlawful detention and goes against the principles of natural justice.

Furthermore, the central government passed the Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act (COFEPOSA) to prevent acts that harm foreign exchange augmentation or conservation, smuggling, or harbouring of smugglers. Under this act, designated officers are authorised to detain any individual, including foreigners.

In the case of Attorney General for India v. Amratial Prajivandas, the Supreme Court deliberated on the constitutionality of COFEPOSA. After careful consideration, the court upheld the act as it serves national interests and state objectives.

Conclusion

In Conclusion, India’s preventive detention legal framework strikes a careful balance between protecting individual liberty and maintaining national security. The growth of these laws has been characterised by judicial interpretations and legislative enactments to address perceived challenges to state interests from the colonial era to post-independence. The limitations of preventative detention are outlined in the constitutional requirements, especially Article 22, which highlights the significance of procedural safeguards in preventing authority abuse.

The jurisprudence of the Supreme Court emphasises the seriousness of preventative detention and calls for rigorous respect for legal frameworks and natural justice principles. The Court has repeatedly upheld the necessity of openness, accountability, and proportionality in detention decisions, even in the face of authorities’ broad powers. The body of case law about preventative detention statutes has shaped our knowledge of the legal and constitutional framework and how these laws are applied.

Furthermore, the interaction of preventive detention legislation with more general societal issues like public order and national security highlights the difficulties in striking a balance between the individual’s rights and the state’s objectives. Preventive detention is a tool for anticipating and addressing threats to public safety and security, but its use must be balanced with respect for legality and fundamental rights.

To uphold constitutional principles and democratic values, examining and enhancing preventive detention laws is imperative. Considering legal, ethical, and practical factors, a thoughtful and balanced approach is necessary to effectively tackle the ongoing challenge of balancing individual freedom and security demands. Ultimately, the success and legitimacy of preventive detention policies hinge on their ability to adhere to the law and preserve the rights and respect of every individual involved.