This article has written by Vaidehi Sharma, a third-year law student currently enrolled in the five-year BALLB program at Mohanlal Sukhadia University.

Introduction-

The intersection of Legal aid and social awareness: Bridging gaps for a just society

The combination of providing assistance and promoting awareness plays a crucial role, in shaping a fairer and more equal world in our modern society. This powerful alliance between support and societal consciousness effectively works towards bridging gaps and addressing injustices. It not ensures access to justice for all but deepens our understanding of the underlying issues that perpetuate inequality.

Legal aid specifically involves offering services to individuals. It serves as a ray of hope for those marginalized by social, economic and unreasonable limitations enabling them to assert their rights and seek remedies. However, the impact of aid extends beyond cases; it intersects with broader social awareness establishing a symbiotic relationship between legal authority and societal consciousness.

Social consciousness, coupled with an encompassing comprehension of issues and a commitment to tackle them acts as a driving force for change. When combined with aid it transforms into a power that challenges oppressive policies and advocates for justice in society. The recognition of inequalities, discrimination and human rights violations fuels these interventions—resulting in more comprehensive and sustainable access, to justice.

This sector holds significance in light of the growing challenges posed by inequality, discrimination and the denial of basic human rights.

Legal assistance serves as a means of transforming understandings into outcomes enabling individuals and communities to effectively navigate intricate legal frameworks. Additionally, it imparts knowledge and fosters active engagement in the field of legal academia.

This intersection plays a role especially when we consider the changing challenges, like economic disparities, discrimination and the denial of basic human rights. Legal aid serves as a means to transform awareness into results empowering individuals and communities to navigate complex legal systems. Additionally, it promotes involvement with the law fostering a sense of understanding that is vital for maintaining a fair and just society.

In terms the connection, between aid and social awareness creates a cycle of mutual influence. Legal aid programs contribute to raising consciousness by highlighting injustices while an informed and socially aware public demands equitable and accessible legal structures. Together they form a relationship that drives society towards justice, fairness and inclusiveness.

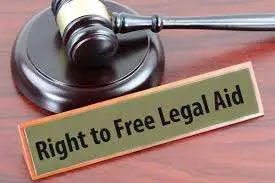

Meaning of Legal aid

Legal aid essentially means providing legal assistance and representation to those who cannot afford it. It works on the principle that each individual should have equal representation regardless of their social or economic status and everyone should have a fair chance to enforce their rights and participate in legal proceedings.

It means that providing adequate means to any unprivileged section of the society for equal and just representation. It encompasses a wide range of government policies, schemes and legislation which aim to bridge the gaps between the privileged section and the unprivileged section by providing them with free help, advice and representation in litigating matters.

Section 2 (c) of The Legal Service Authorities act 1987 defines legal aid which includes the rendering of any service in the conduct of any case or other legal proceeding before any court or other authority or tribunal and the giving of advice on any legal matter.

In India Legal aid apart from government institutions there are specific legal aid organisations, pro-bono lawyers and NGO’s which work towards providing legal aid to the poor and underprivileged sections of society.

Constitutional Status of Legal aid

The preamble to the Indian Constitution aims to secure social, economic and political justice to all individuals. It implies that regardless of the status of an individual the resources, opportunities and privileges should be equally distributed. By providing legal aid services to the marginalised and under-privileged section it aims to address a systematic inequality among individuals.

Fundamental Rights and Legal Aid

A reference can also be drawn from with article 14 of the Indian Constitution which obliges the state to provide equality before law and equal protection of laws. It is the duty of the state to uplift the disadvantaged sections through various legislations and schemes.

This is a constitutional right of every accused person who is unable to engage a lawyer and secure legal services on account of reasons such as poverty, indigence situation and the State is under a mandate to provide a lawyer to an accused person if the circumstances of the case and the needs of justice so require.[1]

The concept of Legal Aid also finds its place under the article 21 of the Indian Constitution which implicitly includes Right to free legal aid as a fundamental right. The two-expression due process of law and procedure established by law under article 21 of the Constitution includes that the procedure should be just, fair and not arbitrary. It implies that the procedure to be adopted in courts should be just to all the parties and the parties should have equal representation.

The court while holding free legal aid as an integral part of article 21 laid down two ingredients of a right to appeal.

- Service of a copy of a judgement to the prisoner in time to enable him to file an appeal.

- Provision of free legal aid to a prisoner who is indigent or otherwise disabled from securing legal assistance.[2]

The right to free legal aid is not only limited to the trial stage. It is the mandatory duty of the state to provide free legal aid to indigent persons at trial as well as appellate stage.

It was held by the Supreme Court that it was the obligation of the court to inquire the accused or convict whether he or she required legal representation at the State expenses. Further the court clarified that neither the constitution nor the Legal Service Authorities Act makes any distinction between a trial and an appeal for the purpose of providing free legal aid to an accused or a person in custody.[3]

The Supreme court held access to justice a facet of rights guaranteed under article 14 and 21 of the Indian Constitution. The following are the main four facets that constitute the essence of access to justice:

- The State must provide an effective adjudicatory mechanism.’

- The mechanism so provided must be reasonably accessible in terms of distance.

- The process of adjudication must be speedy

- The litigant’s access to the adjudicatory process must be affordable.[4]

Directive Principles of State Policy and Legal Aid

Article 39-A was not included in the original draft of the Indian Constitution and its absence was deeply felt by the Indian judiciary from time to time and hence it was inserted by the way of 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act. Article 39-A is not an end goal to be achieved it is a mechanism which makes it obligatory for the State to provide effective machinery for equal administration of justice. The said provision though not justiciable confers a duty on the state to provide free legal aid to all persons by formulating suitable legislations and schemes.

The court held that State is under a constitutional mandate to provide free legal aid to an accused person who is unable to secure legal services on account of indigenous and whatever is necessary for his purpose has to be done by the State. The State may have its financial constraints and its priorities in expenditure but, as pointed out by the court in Rhem v. Malcolm. “The law does not permit any Government to deprive its citizens of constitutional rights on a plea of poverty” and to quote the words of Justice Blackmum in Jackson vs. Bishop, 404 F. Supp. 2d, 571: “humane considerations and constitutional requirements are not in this day to be measured by dollar considerations.”[5]

It was held that in order to achieve the objectives in Article39-A, the state must encourage the participation and support of voluntary organisations and social action groups in operating the legal aid programmes.[6]

Criminal justice system and legal aid

“Indigence should never be a ground for denying fair trial or equal justice… particular attention should be paid to appoint competent advocates, equal to handling complex cases, not patronising gestures to raw entrants at the Bar. Sufficient time and complete papers should also be made available, so that the advocate chosen may serve the cause of justice.”[7]

Under the criminal justice system crimes are always presumed to be against the state. This provision is based on the principle that it is the duty of the state to protect its persons. Thus, when state fails in its duty it owes another duty towards victim to enable them to present their case.

Accordingly, section 24 of the CrPC talks about the appointment of public prosecutors for the purpose of conducting in any court, prosecution, appeal or other proceedings. All the duties including salaries and emoluments to such public prosecutors are paid by the government.

Another notable provision under the Criminal Procedure Code for legal aid is Section 304 now refered under section 341 of Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 which obliges the state to provide legal aid even to the accused persons. Legal aid is to be provided even to accused when it appears to the court that the accused does not have sufficient means to engage pleader.

This section was added by the 1973 Code, which enables the Sessions Court to assign a pleader for the defence of the accused at the expense of the State provided he is unrepresented, and the Court is satisfied that he has no sufficient means to engage a pleader.

This provision is based on the Latin maxim audi-alterum-partem under the theory of natural justice which lays down that every person should have a reasonable opportunity to be heard and to present their case. Depriving an indigent person of presenting his case would be violation of natural justice and would result in grave miscarriage of justice.

The state cannot deny legal aid to an accused on the ground of financial hardships of the state. Legal aid is not just a statutory right under criminal procedure code but it is a constitutional mandate.

It may be noted that the Sessions Judge cannot thrust a counsel of his choice and make the counsel defend the case against the will of the accused.[8]Thus the words ‘of his own choice’ in section 303 of CrPC extend to counsel appointed under Section 304.

The right to legal aid to the accused is not limited to the stage of trial. It arises the moment he is arrested in connection with a cognizable offence.[9] But the said right is only for representing the accused in court proceeding. It does not extend to his interrogation in police custody.

This section enjoins a Court of Session to engage a lawyer, at the expense of the State, for the defence of an accused person who has no means to engage a lawyer. Art. 22(1) of the Constitution, on the other hand, guarantees to the accused his fundamental right to be defended by a ‘legal practitioner of his own choice’. The statutory provision in the present section cannot override the constitutional guarantee under Art. 22(1). In fact, they are analogous.[10]

In the case of Bombay terror attack of 2008, where offer of lawyer was made to him at the time of arrest which he denied and demanded a lawyer from his home country, it was held by the Supreme Court that the action of the accused was nothing but his independent decision. Therefore, on getting convinced that no legal aid was forthcoming from his home country, he made a demand for an Indian lawyer which was immediately provided, it cannot be said that any constitutional right was denied to the accused.[11]

The Supreme held that it is duty of the magistrates and Session Judges in the country to inform every accused who appears before them and who is not represented by a lawyer on account of his poverty or indigence that he is entitled to free legal services at the cost of the State.[12]

The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987

The Legal Services Authorities act, 1987 was enacted to provide free and competent legal services to the weaker sections of the society to ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disabilities, and to organize Lok Adalats to secure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice on a basis of equal opportunity.

Types of Legal Aid Fund under the act

- National Legal Aid Fund- The act authorised for the formation of a Central authority to fund the National Legal aid fund.

- State Legal Aid Fund- The act authorised for the formation of a state authority to fund the State Legal aid fund.

- District Legal Aid Fund- The act authorised for the formation of a District authority to fund District Legal aid fund.

Persons entitled to legal aid under the act

Section 12 of the act lays down the criteria as to who may be entitled to free legal aid under the act. The criteria are as follows;

- Members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes: Persons belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are entitled to legal aid if the case is one of their victimizations.

- Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings or Begar: Individuals who are victims of trafficking in human beings or begar and are economically and socially backward are entitled to legal aid.

- Women and Children: Women and children are entitled to legal aid, particularly in cases of domestic violence, exploitation, and abuse.

- Industrial Workmen: Individuals who are industrial workmen are entitled to legal aid in cases of accidents and occupational hazards.

- Persons in Custody: Persons in custody, including individuals in jails, protective homes, or any other custody, are entitled to legal aid.

- Disabled Persons: Persons with disabilities are entitled to legal aid, ensuring that their rights and interests are protected.

- Persons in Receipt of Annual Income Below a Certain Amount: The government has the authority to prescribe the criteria for determining the annual income of a person entitled to legal aid, and individuals falling below this income threshold may be eligible.

Legal aid schemes under the National Legal Aid Service Authority

There are numerous legal aid schemes under the National Legal Aid Service Authority which are enumerated below[13]:

- Scheme for Para-Legal Volunteers

- Schemes for Legal Services to Disaster Victims through Legal Services Authorities

- NALSA (Victims of Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation) Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Legal Services to the Workers in the Unorganized Sector) Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Child Friendly Legal Services to Children and their Protection) Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Legal Services to the Mentally Ill and Mentally Disabled Persons) Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Effective Implementation of Poverty Alleviation Schemes) Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Protection and Enforcement of Tribal Rights) Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Legal Services to the Victims of Drug Abuse and Eradication of Drug Menace), Scheme, 2015

- NALSA (Legal Services to Senior Citizens) Scheme, 2016

- NALSA (Legal Services to Victims of Acid Attacks) Scheme, 2016

- Legal Services for Differently Abled Children Scheme, 2021

- NALSA’s Compensation Scheme for Women Victims/Survivors of Sexual Assault/other Crimes – 2018

Role of Judiciary in ensuring Legal Aid

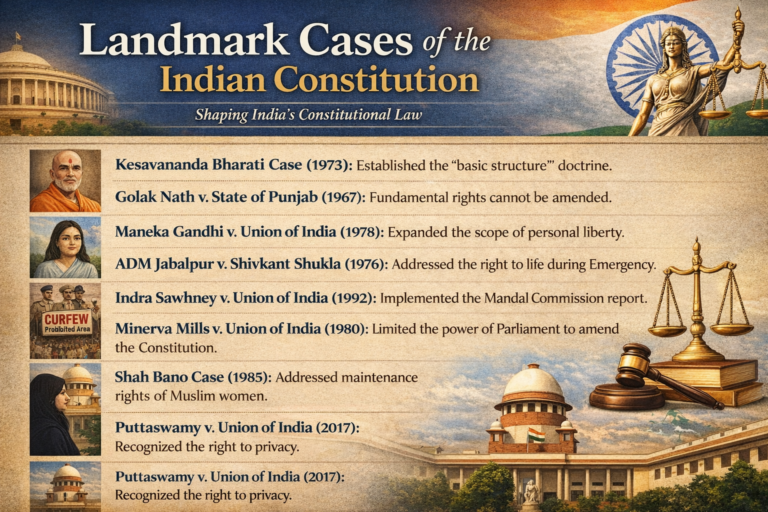

Ever since the commencement of the Indian Constitution judiciary has played an active role in ensuring citizens right. This constructive approach of Indian Judiciary has played a vital role in various areas including Legal Aid services. The supreme court through its liberal interpretation, suo moto cognizance and judicial activism has ensured that right to legal aid is upheld in every trial. The active role of judiciary has very effectively ensured fair trials and access to justice. Through its liberal interpretation the Supreme Court has delivered many landmark judgements which aim towards ensuring the availability of legal aid.

Impliedly including right to free legal aid and speedy trial under the Right to life is a commendable. ‘Man is born with inherent rights’ this very principle has been continuously ensured by the Indian Judiciary. These inherent rights are embodied under article 21 of the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court in the landmark judgment of Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar[14] Supreme Court by taking suo moto cognizance emphasized the constitutional right to free legal aid and speedy trial as an integral part of the right to a fair trial.

The Supreme Court in Gurcharan Singh vs. State of Punjab[15] the Supreme Court reiterated the importance of the right to legal aid in criminal proceedings. The court held that the denial of legal aid to an accused person who is too poor to afford a lawyer would result in an unfair trial, violating the principles of natural justice.

The Supreme Court in State of Maharashtra v. Manubhai Pragaji Vashi[16] considerably widened the scope of the right to free legal aid. The court held that in order to provide free legal aid it is necessary to have well trained lawyers in the country. This is only possible if there are adequate number of law colleges with necessary infrastructure, good teachers and staff. Thus, the court directed the state to provide grant-in-aid to them to function effectively.

Thus, the Supreme Court has extended itself to any extend for a wider implementation of Legal Aid.

Suggested initiatives for more effective implementation of Legal Aid

Though the Indian judiciary and Parliament have laid various legislations, precedents and schemes for ensuring Legal Aid. However there still remains a section of society which needs assistance for the wider implementation of Legal Aid. Following are the suggested measures which may be taken by the courts and legislators to ensure more effective mechanism for Legal Aid:

- Spreading awareness– Though the government has played an active role in imparting its duty for Legal Aid, lack of awareness of such legislations often lead to injustice in many cases. There should be educational camps and seminars to make people aware of the rights they are entitled to.

- Broadening the criteria for Legal Aid- While Section 12 of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 essentially covers all the categories of underprivileged class of people, the scope of criteria should be enhanced to ensure justice to every citizen.

- Anonymous Government Portal: There should be an anonymous government portal for its citizens especially for women so that they can seek legal advice without the fear of society. The victims of sexual offences should be made aware of safeguards available to them.

- Expansion of Legal Aid to all fields of Law and Reasonably Beyond: Traditionally legal aids are confined only to criminal and constitutional matters. This approach should be changed and legal aid should be provided for corporate, IPR and matrimonial disputes etc.

- Mandatory pro bono litigation for every advocate- Provisions should be made to engage all enrolled counsels for a mandatory period of pro- bono litigation for a fixed period. For such practice incentives like tax relaxations, free medical aid in government hospitals should be given to encourage the lawyers.

- Online and hybrid Legal Aid Cells-Online and hybrid legal aid cells should be set up to assist people in legal consultation, documentation etc. Today technology plays a major role in our lives and so to integrate technology into legal aid would be much encouraged step.

- Motivation to Para-legal Players-Tax- relaxation, incentives, free medical aid should be provided to para-legal players to encourage their active participation in Legal Aid.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the nexus between legal aid and social awareness creates a powerful synergy that is pivotal in shaping a more just and equitable society. Legal aid, beyond being a beacon of hope for the marginalized, extends its impact by intersecting with broader social consciousness. This collaboration not only ensures access to justice for all but also deepens our comprehension of the underlying issues fuelling inequality. The alignment of legal aid and social consciousness is a powerful motivator for justice and fairness in society. Providing support and promoting social awareness play an important role in preventing integration gaps and addressing injustice. Legal aid is a beacon of hope for the marginalised, enabling them to assert their rights and find solutions. Lawful help goes about as an impetus, making an interpretation of mindfulness into unmistakable results by engaging people and networks to explore complex general sets of laws. The interweaved connection between legitimate power and cultural cognizance frames a pattern of shared impact. Legitimate guide programs shed light on treacheries, inciting an educated and socially mindful public to request fair and open lawful designs. Together, they push society towards equity, reasonableness, and comprehensiveness.

In the Indian setting, the established acknowledgment of legitimate guide highlights its importance in maintaining the standards of social, financial, and political equity framed in the preface. Central freedoms, especially under Article 14 and 21, stress the state’s obligation to guarantee equivalent portrayal and admittance to equity, regardless of monetary limitations.

The Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987, further institutionalizes the commitment to provide free and competent legal services. Through national, state, and district legal aid funds, the act addresses the diverse needs of individuals, including those from marginalized communities, victims of trafficking, women, children, and persons with disabilities.

The job of the legal executive in ensuring legitimate guide is excellent, with milestone decisions supporting the sacred right to free lawful help. Notwithstanding, to upgrade the viability of legitimate guide, mindfulness crusades, extended qualification measures, and utilizing innovation for online lawful guide cells are proposed drives. Besides, rousing lawful experts, including compulsory free prosecution and motivators for para-legitimate players, can add to a stronger and comprehensive lawful guide framework. At last, these coordinated endeavours plan to connect holes, kill treacheries, and cultivate a general public established on the standards of equity, correspondence, and common liberties.

[1] Suk Das v. Union Territory of Arunachal Pradesh 1986 AIR 991, 1986 SCR (1) 590

[2] M.H Hoskat v. State of Rajasthan AIR 1978 SC 1548

[3] Rajoo alias Ramakant v. State of Madhya Pradesh, AIR 2012 SC 3034

[4] Anita Kushwaha v. Pushap Sudan AIR 2016 SC 3506 at p. 3519

[5] Khatri (II) v. State of Bihar 1981 SCR (2) 408, 1981 SCC (1) 627

[6] Centre of Legal Research v. State of Kerela AIR 1986 SC 1322

[7] Per Krishna Iyer J, in RM Wasawa v State of Gujarat, AIR 1974 SC 1143 : (1974) 3 SCC 581 :

1974 Cr LJ 799.

[8] State v. Sidda 1975 CrLJ 1159

[9] Moti Bai v. State AIR 1954 Raj. 241

[10] Nekram v. State of M.P. (1988)

[11] Mohammed Ajmal Mohammad Amir Kasab v. State of Maharashtra AIR 2012 SC 3565

[12] Khatri (II) v. State of Bihar 1981 SCR (2) 408, 1981 SCC (1) 627

[13] https://nalsa.gov.in/acts-rules/preventive-strategic-legal-services-schemes

[14]AIR 1369, 1979 SCR (3) 532

[15] AIR 1956 SC 460, 1956 CriLJ 827

[16] (1995) 5 SCC 730