This article has been written by Rahul Raheja (student of National law university Nagpur)

RIGHT TO PROPERTY AS LEGAL RIGHT THROUGH CONSTITUTIONAL LENS

INTRODUCTION

Since the dawn of human civilization, property has held a significant value for an individual. Property, in general consensus, is land. However, here property is not confined to land only, rather it means everything which holds an attribute of a property, thus it includes money, gold, etc. by interpretation of hon’ble SC in case of R.C.Cooper v Union of India AIR 1970 SC 564[1], property includes both corporeal and incorporeal things such as land and copyrights or patents respectively. Property helps in accumulating wealth after some investments of time and efforts, improves financial conditions, and the same can be pass upon upcoming posterity to their benefit. But this property is not distributed equally among the masses. Some have a large chunk of land, some own a decent one, and some don’t even possess an acre. This inequality creates generational rifts of wealth and status, be it directly or indirectly. In an emerging economy this inequality possesses a threat. That is why when India got its independence from the hands of the colonizers, the ‘Drafting committee of Indian Constitution’, introduced the concept of fundamental rights and included the right to property in it.

Art 19 (1) (f) provided to citizens to hold, acquire and dispose property within the territory of India. Now these rights were not absolute thus the state holds the power to put restrictions on these when needed. This particular right alongside art 31(A), (B), (C) was removed and later was introduced as a legal right.[2]

At present this right is in art 300A of the Indian constitution. This article says no person shall be deprived of his property saved by authority of law. The State cannot dispossess a citizen of his property except in accordance with the procedure established by law.

According to Art 31 of the Indian constitution it’s said that No individual shall be deprived of his property, unless the law authorizes to do so. This gave the citizens protection so that no government or state can take arbitrary actions against private property. Though the government can do this if it is for public welfare, under the terms of the “Eminent Domain”.

This right went under significant changes throughout the passage of time alongside the various amendments in the Indian constitution. One of the core reasons behind this was the unequal distribution of property across the nation and the paradox created between conserving erstwhile property and ushering into a new egalitarian era by reiterating the equal distribution of land. The researcher will follow onto these details and study these reasons; challenges faced by lawmakers, etc.in the following paper.

RESEARCH PROBLEM

Property rights are one of the most essential rights for any individuals. These rights are the key impetus for a nations overall development. The research problem of this paper will be the “Analysis of property rights, pre and post independence era, and their impact on the legal framework of Indian constitution.” Here the paper will encapsulate historical context of pre independence and post independence property rights. At the same time we it will take a comprehensive analysis of the factors influence historical, legal and socio-economic factors influencing property rights, and it calls for an assessment of how these changes have left an impact on individuals, communities and the broader objectives of the Indian state.

RESEARCH AIM AND OBJECTIVES

- To study the historical context of property rights in India.

- To study the process of incorporating property rights in Indian constitution and its current situation

RESEARCH HYPOTHESIS

In this study, we propose that the shift in the Right to Property within the Indian Constitution, transitioning from a fundamental right to a legal right, can be attributed to the changing objectives of the Indian government. The researcher proposes that this was done by the government which at that time was motivated by a twofold agenda: the facilitation of land reforms and the pursuit of social justice, all while maintaining q delicate balance with individual property rights. Here, the working hypothesis is that these legal transformations have had substantial repercussions for property owners and the broader socio-economic landscape. Through an examination of the historical and legal evolution of property rights in India, we seek to assess whether these amendments mirror India’s

Commitment to achieving a fairer distribution of land and resources while adapting to the evolving dynamics of a developing nation. Furthermore, the aim is to evaluate how these legal changes impacted property rights, which includes individual freedoms, economic development, and social stability.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- What were the property rights in India?

- How property rights were included in constitution of India?

- How 44th amendment was introduced which later changed the framework for property rights?

SCOPE AND LIMITATIONS

SCOPE:

The project will undertake an extensive historical and legal examination of property rights in India. It will map the transformation of property rights from the pre-independence period to the post-independence era, encompassing notable amendments along the way. The project will delve into the consequences of pivotal amendments, with a particular focus on the Forty-Fourth Amendment Act of 1978. It will analyze how these legal changes have influenced property rights, individual liberties, economic progress, and societal stability.

RATIONALE OF STUDY:

Examining the “Right to Property in the Constitution of India” is of paramount importance for several compelling reasons. This investigation unravels the historical progression of this right, marked by a pivotal shift through the 44th Amendment Act of 1978. It aids in comprehending the constitutional significance, offering insights into how the Indian Constitution strikes a balance between individual property rights and the welfare of society.

The study allows for a comprehensive understanding of its impact on citizens, encompassing property ownership, land reform, and economic development, thereby elucidating the practical consequences of these constitutional modifications. Legal aspects, including notable cases related to land acquisition and property owners’ rights, add depth to the exploration. Furthermore, it has far-reaching socio-economic implications, contributing to conversations on social justice, equity, and national development.

By delving into the political motivations and debates surrounding this right, this research underscores its role in shaping governmental priorities. A comparative examination with international approaches to property rights provides global context, while the contemporary relevance of property-related issues underscores the enduring significance of this inquiry. For legal scholars and policymakers, this serves as a valuable resource for developing legal theory, offering policy recommendations, and fostering informed public discussions. Ultimately, this study serves educational purposes, enhancing understanding among law students, scholars, and the general public regarding this fundamental facet of India’s constitutional framework. In sum, the investigation into the right to property in the Indian Constitution is multifaceted and offers invaluable insights into the nation’s legal and socio-political landscape.

PROPERTY RIGHTS IN INDIA

The pre-independence era in India was marked by a complex and multifaceted system of property rights deeply embedded in the country’s historical, cultural, and socioeconomic structure. These property rights played a pivotal role in shaping the economic and social landscape of the subcontinent. Later, we will delve into the various forms of property rights that prevailed in pre-independence India.

As one can guess, one of the prime usages of lands was carried out by the Agrarian society and this society was prevalent throughout the Indian subcontinent. It not only helped them to create livelihood but also a generational wealth which lasted for years to come. This made land ownership a pivotal point in property rights. However, these rights were not the same for everyone. Various groups of individuals possessed differing degrees of land ownership rights. As an example, Zamindars were generally prominent landholders tasked with the collection of taxes from peasants. At the same time these peasants were the ones who actually cultivated the land, but they don’t own it. However, they were protected from arbitrary eviction. Collective land ownership was deeply embedded in the social structure of rural India, where choices concerning land utilization and distribution were determined through communal decision-making procedures. The British colonial administration introduced various land tenure systems that had a profound impact on property rights in pre-independence India. For example, the Permanent Settlement of 1793 fixed land revenue rates, leading to the emergence of a new class known as Zamindars, who acted as intermediaries. In certain regions, the Ryotwari System was implemented, granting land rights directly to individual cultivators, eliminating intermediaries. India’s diverse religious landscape saw the establishment of extensive properties owned by religious institutions such as temples, mosques, churches, and managed by religious trusts, playing a pivotal role in supporting religious activities and charitable causes. Property rights were significantly influenced by caste-based restrictions, with specific castes often facing limited access to land ownership and being confined to cultivating land owned by higher-caste landlords.

The era of British colonial rule had a profound impact on property rights before India gained independence. Policies related to land revenue, land surveys, and changes in land tenure systems frequently led to conflicts and unrest. The Indian Rebellion of 1857, in part, arose from discontent regarding property rights and land ownership issues. Tribal and indigenous communities typically followed customary laws and traditions that governed property rights. Tenancy laws were introduced to safeguard the rights of tenants, providing a degree of security in tenure and curbing landlords’ ability to evict tenants arbitrarily. Gender dynamics played a crucial role in property rights, with women often encountering restrictions on their ability to inherit or possess property. Social reform movements, led by influential figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, aimed to address gender disparities in property rights. .

At the end one can conclude that, before gaining independence, India exhibited a varied tapestry of property rights shaped by historical, cultural, and socioeconomic elements. These property rights were intricately linked to India’s societal framework and carried substantial consequences for the economic welfare of both individuals and communities. The complexities of pre-independence property rights continue to influence land and property-related discussions in modern India in our history books. All of us have heard of Zamindari or Ryotwari systems till now. These systems were prevalent in older eras across the country. The Zamindari system, which can be traced back to medieval India, was introduced by the Mughals, where these zamindars were responsible for collecting revenue and taxes from the villages they administered. After the decline of Mughals and emergence of EIC, there was a significant change in zamindari system, in which their powers were increased incredibly by bestowing them with the hereditary rights on lands so as to ensure their loyalty and productivity in collecting the revenue for the crown’s in practice and were supposed to invest in their lands so as to maximize the productivity and keep the profits. Thus, the zamindars then used to give that land to a peasant to work on it and in return that peasant would give the hefty tax levied on them. If somehow one is unable to pay the imposed tax, then he would be replaced. In this way it became easier for the crown to collect taxes as it’s more productive to collect it from thousands of zamindars rather than millions of peasants. Also, as the peasants were given no rights on that land. Now what happened was that these giant Zamindars would enjoy their enormous amounts of land. However, those who work at these lands, who tilled them, do not own a single acre for themselves. This made the rich richer and poorer. This rift, generation after generation, created so many economic differences between social strata that it eventually posed a threat to our economy. [3]

INCLUSION OF PROPERTY RIGHTS IN CONSTITUTION (1950)

The incorporation of the Right to Property into the Indian Constitution in 1950 represented a momentous milestone in the country’s history. This fundamental entitlement, initially codified in Article 31, aimed to protect the property of citizens from arbitrary encroachments by the government. However, as time passed, pivotal amendments, notably those made in 1951 and 1978, altered the nature and scope of this right, reflecting the evolving objectives of the Indian government.[4]

The framers of the Indian Constitution recognized the importance of property rights in a society that encompassed diverse ownership structures, ranging from prosperous Zamindars to small-scale cultivators. The inclusion of the Right to Property as a fundamental right reflected an acknowledgment of the imperative to safeguard these rights in the post-independence period. Article 31 of the Constitution guaranteed the Right to Property as a fundamental right, affirming that “no person shall be deprived of his property saved by the authority of law.” This provision was designed to protect the property of citizens from unjust confiscation by the state and emphasized the fundamental principle that property could only be deprived through lawful procedures. Nonetheless, the initial Article 31 underwent substantial transformations through significant amendments, primarily driven by the government’s commitment to enact land reforms and social justice policies.

The First Amendment Act of 1951 represented the initial substantial alteration to the Indian Constitution and had a profound effect on the Right to Property. This amendment introduced Article 31A, granting the government the authority to enact laws pertaining to agrarian reforms and the acquisition of estates and other properties, even if such legislation infringed upon the Right to Property. The First Amendment validated laws related to the abolition of the zamindari system and other land reform measures, which might otherwise have been deemed unconstitutional. The Fourth Amendment Act of 1955 placed further limitations on property rights. Article 31B was introduced, giving precedence to laws enacted to fulfill the Directive Principles of State Policy over the Right to Property. This implied that laws aimed at achieving social and economic justice could take precedence over property rights. The Seventeenth Amendment Act of 1964 broadened the state’s powers in matters related to proper. Then the Seventeenth Amendment Act of 1964 extended the state’s jurisdiction in property-related affairs.

The most profound transformation of the Right to Property occurred with the enactment of the Forty-Fourth Amendment Act of 1978. This amendment removed the Right to Property from the list of fundamental rights within the Constitution. Although it persisted as a legal right under Article 300A, it no longer retained its status as a fundamental right. Article 300A was introduced to protect property rights but placed them within a different context. It affirmed that “no person shall be deprived of his property saved by authority of law,” emphasizing the legal foundation for safeguarding property.

The consequences of these amendments reshaped the Right to Property from a robust fundamental right to a legal right, subject to constraints imposed by the state in pursuit of land reforms and social justice. These amendments mirrored India’s commitment to achieving a fairer distribution of land and resources, while simultaneously harmonizing individual property rights with the priorities of a developing nation.

In summary, the incorporation of the Right to Property into the Indian Constitution in 1950 represented a seminal moment in the protection of property rights. However, subsequent amendments, especially those in 1951 and 1978, redefined its scope and character, underscoring that property rights needed to align with the broader objectives of advancing social justice and land reforms. These amendments significantly influenced the legal framework surrounding property rights in India, reflecting the changing priorities of the nation. Let us look at the road to the 44th amendment.

ROAD TO 44TH AMENDMENT

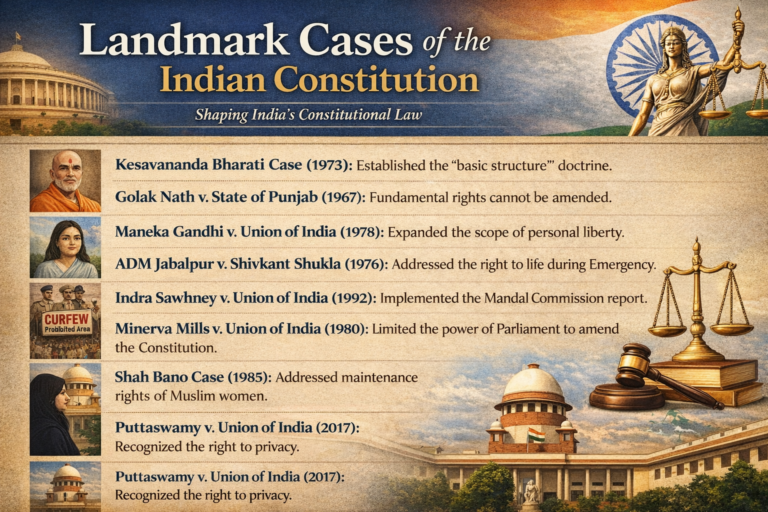

This case was proven helpful for the abolition of the right to property as a legal right of the Indian constitution. The main issue before hon’ble supreme court India in this case was whether the parliament of India with the amending[5]g powers of article 368 can amend fundamental rights or not. Before this judgment came the same argument was raised in three different cases which were ” Shankari Prasad v union of India,”” Sajjan Singh v State of Rajasthan[6],”” I.C Golaknath v State of Punjab”.

In Shankari Prasad v Union of India,1st constitutional amendment of 1951 was challenged in front of hon’ble court, which safeguards laws pertaining to land acquisition and appropriation. Hon’ble court dismissed the arguments raised by the petitioner in this case, which stated that constitutional amendments were subject to Art 13, by saying that constitutional amendments cannot be subjected to some ordinary laws.

In the case of “Sajjan Singh v State of Rajasthan, the same contentions were raised. Here also the court opined to the fact that parliament cannot amend fundamental rights as it would be a use of unlimited power. Further stating that the framers of constitution conferred parliament with the powers to put limitations of these rights and not completely abolish it because special majority is in the opinion [7]to do so. Justice M. Hidayatullah and Justice Mudholakar held that these fundamental rights cannot be amended. The reason being that these rights were too essential and fundamental that they are not supposed to be amended like the other laws in Indian constitution by the amending powers of article 368.thus this case did reaffirm the previous judgment.

However, in the case of “I.C.Golaknath v state of Punjab”, the two previous decisions were overruled by the hon’ble SC. While giving the judgment, Chief Justice Rao gave the basic difference between any ordinary law and constitutional law. He said, “While articles of less significance would require consent of most States, fundamental rights can be dropped without such consent.” While a single fundamental right cannot be abridged or taken away by the entire Parliament unanimously voting to that effect, a two-thirds ‘majority can do away with all the fundamental rights.”. In addition, the Hon’ble court held that every change made in accordance with art 368 would fall except for art 13, which states that any law which counters or violates fundamental rights would be null and void.

But as art 13 is subjected to ordinary laws and thus can be altered, parliament by using its amending powers amended it and added art 13(4) which clearly overrides its former provision of not validating the amendments under 368. Further these amendments cannot be challenged by using 13. Similar amendments were clause (4) to Article 13, which overrides the provision that any amendment under Article 368 would not be challenged under Article 13 of the Constitution. In order to remove all existing ambiguity, Parliament added clause 3 to Article 368 stating that “Nothing in Article 13 shall apply to any amendment made under this article.”

Now the case that was the final nail in the coffin was “Kesavananda Bharati v state of Kerala[8]

In this landmark judgment, hon’ble SC held that yes, we can amend fundamental rights keeping the “Doctrine of basic structure”. This decision was 7:6, where Justice Khanna’s decision played a crucial role. The bench was divided into groups with different opinions. One was of the opinion that parliament can amend the fundamental rights because the power to amend under art 368 itself was a constitutional power and not an ordinary one. Reasoning being that these powers were extended to each article of the Indian constitution. Whereas the second group opined that no, we cannot amend fundamental rights in the sense of completely eradicating them, though we can restrict them to certain extent. Justice Khanna supported both arguments to some extent. But later on, while overruling the case of I.C.Golaknath v State of Punjab, his opinion was that the “Doctrine of basic structure “should be considered while making these amendments. Further emphasizing that parliament should envisage the image of the old constitution. Thus, limiting parliament is taking arbitrary decisions and giving them the liberty to do what is needed, in a proper way. This balanced rationale was appreciated throughout the nation and made this judgment so crucial while considering amendments in fundamental rights.

CONCLUSION

The inclusion of the Right to Property in the Indian Constitution is a testament to the nation’s evolving socio-economic landscape and its commitment to balancing individual property rights with broader societal interests. The journey of property rights in India, from pre-independence to post-independence, reflects a complex tapestry of historical, cultural, and legal factors that have left an indelible mark on the nation’s development.

The pre-independence era was characterized by a diverse landscape of property rights, influenced by factors such as the zamindari system, communal landownership, caste-based restrictions, and customary laws. The British colonial rule introduced significant changes through policies like the Permanent Settlement of 1793 and the Ryotwari System. While these policies had various impacts, they often led to conflicts and social unrest. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was, in part, a response to discontent related to property rights and landownership issues. As India moved toward independence, customary laws, tenancy laws, and social reform movements aimed to address disparities in property rights, especially concerning women and marginalized communities.

The most significant transformation of the Right to Property came with the Forty-Fourth Amendment Act of 1978, which redefined it as a legal right, no longer considered a fundamental right. While Article 300A was introduced to safeguard property rights, it placed them in a different context, emphasizing the legal framework for property protection. These amendments were motivated by the government’s pursuit of land reforms and social justice policies, reflecting India’s dedication to achieving a more equitable distribution of land and resources.

The importance of property rights cannot be overstated. These rights are fundamental for several reasons. They drive economic development by providing security for investments and innovation, promoting wealth distribution, and ensuring social stability. Secure property rights also have a direct impact on individual freedom, encouraging responsible resource management and sustainability. They facilitate borrowing and lending, fostering entrepreneurship and innovation, and they are a cornerstone of the rule of law. Property rights, in essence, are a bedrock of prosperous, stable, and equitable societies.

As we’ve explored the historical and legal journey of property rights in India, it is clear that the nation’s commitment to achieving social justice and equitable land distribution has been a driving force behind legislative changes. The transition from a fundamental right to a legal right underscores the necessity of harmonizing individual property rights with broader societal objectives. While this change has had implications for property owners, it reflects a nation’s evolving priorities in pursuit of a more just and equitable society.

In conclusion, the Right to Property in the Indian Constitution is a dynamic and evolving concept, shaped by historical, cultural, and legal factors. The amendments made to it over the years demonstrate India’s dedication to achieving social justice, equitable land distribution, and sustainable development. In this process, property rights have been redefined, moving from fundamental rights to legal rights, highlighting the complex balancing act between individual liberty and the collective well-being of the nation.

As India progresses, the story of its property rights continues to be written, reflecting the ever-changing dynamics of its society, economy, and governance. Property rights remain a cornerstone of its journey towards a more just and equitable future.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Research paper:

Wahi Namita, The Fundamental Right to Property in the Indian Constitution (August 10, 2015).

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2661212 or https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2661212

,

Ms. Legha Mamta Ranjitsingh Right to Property in India: A Journey from Fundamental Right to mere Constitutional Right

https://www.jetir.org/view?paper=JETIR1901C18

[1] Ms.Kishita Gupta, Right to property as a Constitutional right

[1] R.C.Cooper v Union of India AIR 1970 SC 564

[2]Right to Property and its Evolution in India

[3] Ms.Kishita Gupta, Right to property as a Constitutional right

[4] Namita Wahi, The Fundamental Right to Property in the Indian Constitution.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2661212

[5] I.C.Golaknath v State of Punjab

[6] Sajjan Singh v State of Rajasthan

[7]Shankari Prasad v Union of India

[8] Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala

https://judgments.ecourts.gov.in/KBJ/?p=home/intro