Maritime Disputes in the South China Sea: Lawfare under UNCLOS Analyzes legal tactics used by claimant states and implications for maritime peace.

Abstract

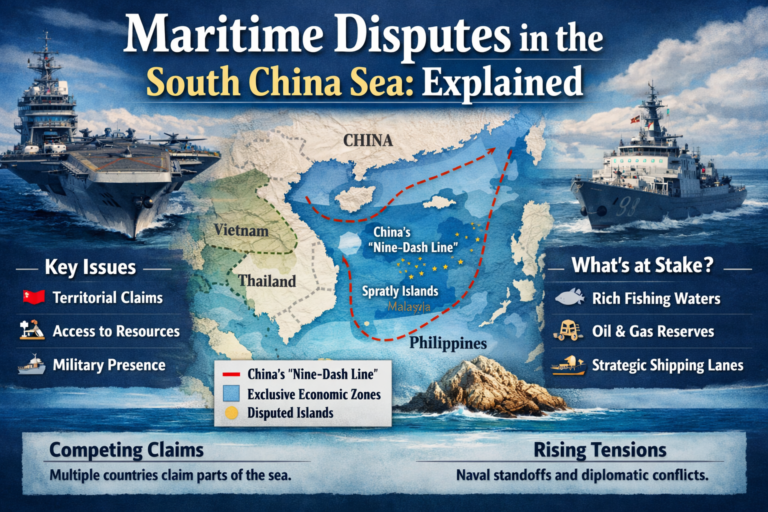

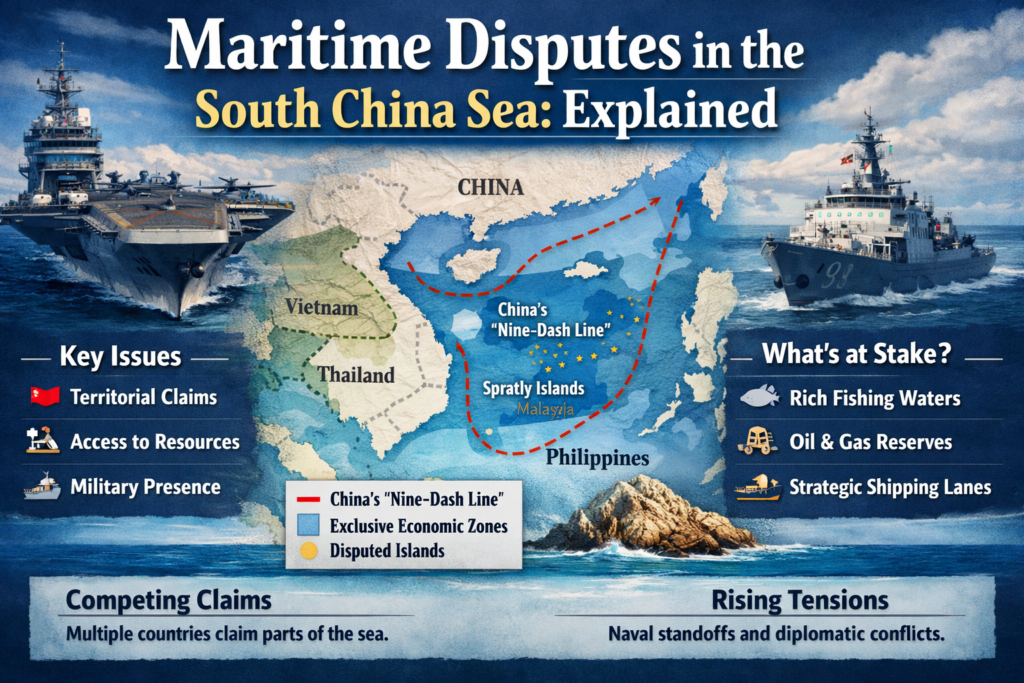

This paper examines the deployment of lawfare as a primary strategy in contemporary maritime disputes in the South China Sea (SCS), within the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It assesses how claimant states, principally China, employ legal language and selective engagement with international law to assert expansive territorial and resource claims, most notably via the nine-dash line, reinterpretation of baselines, and sustained ambiguity. Concurrently, Southeast Asian states, such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia, have utilized UNCLOS mechanisms, including arbitration and submissions to the CLCS, to counterbalance China’s claims. The tactics examined include instrumental legal interpretations, arbitration initiatives, Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs), and bilateral versus multilateral dispute resolution mechanisms. The paper then discusses the wider implications on regional stability, legal norms, and the prospects for maritime peace, considering the limits of enforcement and the rise of grey‑zone coercion. It argues that while lawfare has expanded normative tools for smaller states, its strategic instrumentalization by powerful actors risks undermining UNCLOS norms and exacerbating instability.

Keywords: maritime, law, UNCLOS, sea disputes, lawfare, states

Introduction

The South China Sea (SCS) is sought after for its fisheries, hydrocarbon reserves, and strategic maritime routes. Under UNCLOS, coastal states have rights to a 12‑nautical‑mile territorial sea and a 200‑nautical‑mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Still, disputes persist over maritime entitlements, especially where features are low‑tide elevations or reefs that cannot sustain habitation and thus do not qualify as “islands” under Art. 121(3) UNCLOS[1].

Since the 1980s, China has claimed roughly 80% of the SCS via the nine-dash line, asserting “historic rights” that contradict UNCLOS[2]. The Philippines’ 2013 arbitration initiated under UNCLOS resulted in a 2016 PCA award invalidating China’s expansive claims and clarifying that many disputed features are legally “rocks” or low‑tide elevations[3].

The concept of lawfare, using legal mechanisms strategically to gain political advantage, is increasingly central to the SCS disputes. This paper examines how both China and smaller claimant states employ lawfare, and what this means for maritime peace.

China’s Lawfare Tactics under UNCLOS

- Reframing Legal Tools and Assertions

After the PCA ruling, rather than withdrawing its claims, China issued a series of Notes Verbales to the UN Secretary‑General (2020–2021) invoking “general international law” and “outlying archipelagos” to justify baselines and continental shelf claims beyond UNCLOS limits, even though UNCLOS explicitly regulates baseline drawing and EEZ entitlements.

This reflects a dual or selective approach: China continues to ratify and refer to UNCLOS when it suits its aims, e.g., against FONOPs by the U.S., yet rejects PCA findings when adverse[4].

- Maritime Militia, Cabbage Tactics, and De Facto Control

China’s legal claims are bolstered by “grey‑zone” coercion using its People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) and Coast Guard, backed by navy support. These forces encircle contested islands in layers, a strategy known as “cabbage tactics”, to physically establish control and deter rival access, while remaining below the threshold of armed conflict[5].

Instances like the Hai Yang Shi You 981 standoff in 2014 (China’s oil rig in Vietnam’s claimed EEZ, escorted by hundreds of vessels) illustrate how state-sponsored maritime activity co-opts legal ambiguity to assert control without formal sovereignty claims[6]. Similarly, the Whitsun Reef incident in 2021 saw over 200 Chinese fishing vessels (allegedly militia) gathering at disputed reefs, prompting diplomatic protests from the Philippines and Vietnam.

- Information, Research, and Institutional Legitimacy

China has invested in legal discourse through sponsorship of research institutions (e.g., the National Institute for SCS Studies) and domestic legal scholarship that challenges PCA findings and promotes its own interpretations under “general international law,”[7]. This constitutes lawfare in the ideological/institutional domain, seeking to shape normative understanding.

Lawfare by Southeast Asian States under UNCLOS

- Arbitration and CLCS Submissions

The Philippines led the legal offensive by initiating arbitration in 2013, culminating in the 2016 PCA ruling that China’s nine-dash claims are invalid and asserting Manila’s sovereign rights in its EEZ[8].

Vietnam and Malaysia (sometimes jointly with Vietnam) have used CLCS submissions and technical UNCLOS-based legal channels to clarify continental shelf limits – steps considered lawfare insofar as they employ UNCLOS tools to solidify legal claims and counter China’s broader assertions.

Indonesia, though not a claimant state over features like the Spratlys, welcomed the arbitration outcome and adopted a restraint-based diplomatic approach, emphasising clarification and urging compliance rather than confrontation. It reaffirmed that China’s nine-dash line lacks a basis under UNCLOS, even after bilateral economic agreements prompted domestic criticism.

- Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs)

The United States, along with allies like Australia, conducts FONOPs to reinforce UNCLOS norms by sailing or flying in areas claimed by China as territorial seas, including within 12-mile zones around artificial islands. Though the U.S. has not ratified UNCLOS, it treats the Convention as customary international law and counters China’s encroachments via these operations[9].

Some analysts critique FONOPs as lawfare by the U.S., since they instrumentalise legal norms to serve geopolitical aims and project maritime dominance, raising questions about reciprocity and escalation.

- Multilateral and ASEAN Approaches

Many ASEAN states emphasise multilateralism and uphold UNCLOS formally in regional statements, such as the June 2020 ASEAN leaders’ statement, reaffirming non-militarisation and self-restraint in maritime conduct[10]. This represents a collective lawfare posture grounded in affirmation of legal norms as a means to preserve regional stability.

Comparative Legal Tactics & Lawfare Dynamics

The lawfare strategies adopted in the South China Sea reveal a stark contrast in how different actors interpret and instrumentalise international maritime law. China has employed a complex mix of legal and quasi-legal tactics to reinforce its expansive maritime claims. These include invoking the ambiguous “nine-dash line,” asserting “historic rights,” and issuing Note Verbales that selectively reference general international law while avoiding full compliance with UNCLOS obligations[11]. In tandem, it deploys a maritime militia and uses “cabbage tactics”, a layered encirclement of disputed features, to establish de facto control while avoiding overt military escalation[12]. This form of lawfare is marked by strategic ambiguity and deliberate legal reinterpretation. On the other hand, Southeast Asian claimant states such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia have adopted a more rules-based approach. The Philippines spearheaded the legal pushback through its 2013 arbitration case against China under Annexe VII of UNCLOS, resulting in the landmark 2016 PCA ruling[13]. Vietnam and Malaysia, meanwhile, have utilised submissions to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to define maritime boundaries in accordance with UNCLOS[14]. These states use legal channels to reinforce their entitlements and to delegitimise China’s claims within established international norms. The United States, though not a party to UNCLOS, has conducted Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) as a form of legal signalling to contest what it considers excessive maritime claims, including those around China’s artificial islands[15]. Such operations, while grounded in customary international law, also reflect an assertive form of legal projection by a non-party. Meanwhile, ASEAN as a collective has emphasised multilateral diplomacy and the centrality of UNCLOS through declarations and summit communiqués that call for restraint, demilitarisation, and the peaceful resolution of disputes[16]. Together, these varied approaches underscore how lawfare, whether by coercion, litigation, or normative assertion, has become a defining feature of the South China Sea disputes, reflecting both the potential and the limitations of international legal mechanisms in contested maritime regions.

Implications for Maritime Peace

- Strengthened Normative Tools and Legal Precedents

The 2016 PCA ruling reaffirmed UNCLOS as central to resolving maritime disputes, clarifying definitions of islands, rocks, and low-tide elevations. This has created legal precedents that future claimants and tribunals can invoke[17].

Smaller states have acquired legal leverage and international legitimacy by using UNCLOS-based processes, reducing reliance on bilateral power balances or coercion.

- Enforcement Deficits and Norm Erosion

China’s continued island-building, militia presence, and refusal to accept the PCA decision demonstrate the enforcement weakness of UNCLOS. Powerful states can disregard rulings without direct consequences, undermining legal authority.[18]

China’s reinterpretation of legal norms (via “general international law”) risks establishing parallel legal standards, weakening UNCLOS’s universality and emboldening other states to reinterpret its provisions[19].

- Grey‑Zone Conflict and Escalation Risk

Maritime militia and coast guard assertiveness blur the line between legal activity and coercion, making it harder for claimants to respond without risk of escalation. Such grey‑zone tactics are designed to avoid armed conflict while changing facts on the ground[20].

The use of ramming, water cannons, and lasers, as documented in the 2014 Hai Yang rig standoff and recurring Philippine encounters, illustrates how legal ambiguity enables hostile interactions short of war.

- Regional Polarisation and External Power Play

U.S. and allied FONOPs, while intended to assert legal norms, also risk geopolitical friction and may be perceived as escalatory by Beijing[21].

Some critics argue that external lawfare exploits UNCLOS norms to advance strategic interests, potentially undermining ASEAN states’ autonomy and complicating regional diplomacy[22].

Policy Recommendations

- Strengthen ASEAN legal coordination: Southeast Asian claimant states should harmonise their maritime claims, legal submissions, and diplomatic messaging to reinforce UNCLOS norms multilaterally instead of bilateral bargaining with China (as endorsed in ASEAN 2020 statements).

- Expand capacity building: Regional partners and external powers should support domain awareness, maritime patrol capacity, and legal expertise in littoral nations to effectively monitor incursions and assert UNCLOS-based rights.

- Condition enforcement on reciprocity: States should communicate that restraint in FONOPs could be balanced with reciprocal behavior by China, potentially fostering mutual de-escalation frameworks.

- Promote UNCLOS ratification and global support: Countries like the U.S. should ratify UNCLOS formally to avoid undermining its moral authority and strengthen the universality of maritime law.

- Guard against selective lawfare misuse: The international community and legal scholars should challenge strategies that seek to reinterpret UNCLOS beyond its negotiated terms, while supporting legal actions grounded in its provisions.

Conclusion

Lawfare under UNCLOS has become a central battleground in the South China Sea disputes. China’s strategy of legal ambiguity, through historical rights, reinterpretation of baselines, and maritime militia deployment, seeks to operationalise claims without consent. Meanwhile, Philippine arbitration, CLCS submissions, and ASEAN normative coordination represent legitimate lawfare by smaller states to stabilize and clarify rights within the UNCLOS legal order.

However, without robust enforcement, lawfare risks fragmenting UNCLOS norms and escalating tensions via grey‑zone tactics. The stability of the region now depends on strengthened capacity, collective legal coordination, and balanced use of maritime operations to reinforce legal norms while avoiding coercive escalation. In this evolving legal theatre, maritime peace rests on firm adherence to UNCLOS, equitable dispute resolution, and vigilance against strategic legal distortion.

[2] Chicago Journal of International Law

[3] Modern Diplomacy+2Chicago Journal of International Law+2GIGA Hamburg

[4] Taylor & Francis OnlineEast Asia Forum

[5] Douglas Guilfoyle, “The Rule of Law and Maritime Security: Understanding Lawfare in the South China Sea”, Int’l Affairs (2019).

[6] Columbia Undergraduate Law Review.

[7] Chicago Journal of International Law

[8] Permanent Court of Arbitration, Philippines v. China, Award on Jurisdiction and Merits (2016).

[11] See U.N. Secretary-General, Communications Received from China and Other States Concerning the South China Sea (2020–2021), U.N. Doc. A/74/548; Christian Schultheiss, What Has China’s Lawfare Achieved in the South China Sea, ISEAS Perspective No. 2023/51 (May 2023), https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective// 2023-51-what-has-chinas-lawfare-achieved-in-the-south-china-sea.

[12] See Andrew S. Erickson & Conor M. Kennedy, China’s Maritime Militia: What It Is and How to Deal with It, Foreign Affs. (June 23, 2016); Bill Hayton, The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia 174–75 (2014).

[13] See In the Matter of the South China Sea Arbitration (Phil. v. China), Case No. 2013-19, Award (Perm. Ct. Arb. July 12, 2016); Douglas Guilfoyle, The Rule of Law and Maritime Security: Understanding Lawfare in the South China Sea, 95 Int’l Aff. 999, 1004–05 (2019).

[14] See Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, Outer Limits Submissions by Malaysia and Vietnam, https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/submission_mysvnm_33_2009.htm (last visited July 19, 2025).

[15] See U.S. Dep’t of Def., Annual Freedom of Navigation Report to Congress for Fiscal Year 2023 (Jan. 2024); James Kraska, The Law of the Sea Convention: A National Security Success—Global Strategic Mobility Through the Rule of Law, 39 Geo. Wash. Int’l L. Rev. 543, 554–58 (2007).

[16] See ASEAN, ASEAN Chairman’s Statement on Maintaining Peace and Stability in Southeast Asia (June 2020), https://asean.org; Lynn Kuok, The ASEAN Way and the South China Sea, Brookings Inst. (Nov. 2022), https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-asean-way-and-the-south-china-sea//

[17] Columbia Undergraduate Law Review

[18] Chicago Journal of International Law.

[19] Christian Schultheiss, “What Has China’s Lawfare Achieved in the South China Sea?”, ISEAS‑Yusof Ishak Perspective 2023/51 (2023).

[20] Lieber Institute West Point