This article has been written by Jefferson Paul R, a law student from CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bangalore.

|

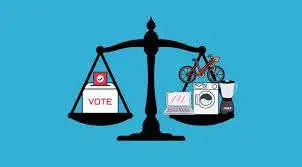

ABSTRACT The introduction of the None of the Above (NOTA) option in Indian elections was heralded as a paradigmatic shift in the country’s electoral landscape, purportedly aimed at empowering voters and fostering electoral accountability. However, a critical examination of the NOTA option reveals that its efficacy has been compromised by its inability to exert a tangible impact on electoral outcomes, thereby undermining its objective of promoting voter empowerment and electoral accountability. This article undertakes a nuanced analysis of the limitations of NOTA in Indian elections, interrogating the normative and institutional factors that contribute to its ineffectiveness. Through a comprehensive review of the electoral laws and regulations governing the NOTA option, this article argues that the absence of a correlative right to reject all candidates has rendered the NOTA option nugatory, perpetuating a democratic deficit in India. Furthermore, the article posits that the NOTA option has been reduced to a mere symbolic gesture, failing to provide voters with a meaningful alternative to the candidates on the ballot. The article also examines the implications of the NOTA option’s ineffectiveness, including the perpetuation of a cycle of corrupt politics and the erosion of voter trust in the electoral process. The article concludes by advocating for reforms aimed at revitalizing the NOTA option, including the institution of a proportional representation system and recall elections. These reforms, the article argues, are essential to promoting a more transparent and accountable electoral process in India, and to ensuring that the NOTA option serves as a meaningful tool for voter empowerment and electoral accountability. KEYWORDS: Electoral accountability, Electoral reform, Indian democracy, Indian elections, NOTA, Right to reject, Voter empowerment. |

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of the None of the Above (NOTA) option in Indian elections was hailed as a significant reform, aimed at empowering voters and promoting electoral accountability. However, despite its promising beginnings, NOTA has failed to live up to its intended purpose. While the introduction of NOTA was seen as a step towards electoral reform and empowering voters to express their dissatisfaction with the available candidates, its effectiveness in truly impacting the outcome of elections has been questioned. In several instances, NOTA has garnered a majority of votes, only to be rendered ineffective in influencing the election outcome. This article delves into the limitations of NOTA in Indian elections, examining the reasons behind its ineffectiveness and the implications for the democratic process.

THE CONCEPT OF NOTA

NOTA was introduced in India through the Supreme Court’s judgment in the case of People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India (2013)[1], where the court saw that the right to freedom of speech and expression granted under Article 19 (1) (a)[2] of the Constitution includes the right of a voter to not vote for any candidate in the elections. As a result, the Apex court directed the Election Commission of India (ECI) to provide a NOTA (None Of The Above) option on electronic voting machines (EVMs) and ballot papers, allowing voters to reject all candidates contesting an election. This emphasized the right to privacy of the individuals who show up at the polling booths and still reject all the candidates contesting in the election. The decision by the Apex Court increased the accountability of the political parties in nominating sound candidates to stand for the poll. The NOTA option was seen as a means to promote electoral accountability, encourage clean politics, and provide voters with a sense of empowerment. The NOTA option has been appreciated since then, it promoted the right to privacy of the votes in the same place hoisting a right to reject all the candidates. The basic understanding behind NOTA is that the option enabled the votes to convey the political parties to make a wiser decision in the nomination of members more accountable.

THE LIMITATIONS OF NOTA

Despite its noble intentions, NOTA has several limitations that render it ineffective in influencing election outcomes. The primary limitation is that, in an event that if NOTA receives a majority of votes, the second-highest candidate will still be declared the winner of the respective constituency. This means that the NOTA votes are essentially wasted, as they do not lead to the rejection of all candidates or the holding of fresh elections. Another limitation of NOTA is that it does not provide a clear alternative to voters. In the absence of a viable alternative, voters are forced to choose between a limited scope of candidates, leading to a situation where the least undesirable candidate is elected. This defeats the purpose of NOTA, which is to promote electoral accountability and encourage clean politics.

The true potential of NOTA remains untapped due to a glaring loophole in the Representation of the People Act, 1951. Section 62 of the Act grants citizens the right to vote, but it does not provide for the right to reject all candidates[3], rendering NOTA a mere symbolic gesture. The Law Commission of India’s 255th report had recommended incorporating the right to reject all candidates into the Act[4], but this suggestion remains unimplemented. Until the government amends the Act to give NOTA a significant power, it will continue to be a toothless tiger, unable to bring about meaningful change in the electoral landscape. By incorporating the right to reject all candidates, the government can make NOTA a powerful tool for voters to demand better representation and hold politicians accountable. Additionally, the lack of legal provisions mandating a re-election or disqualification of candidates in case NOTA secures the highest number of votes further undermines its efficacy.

THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF NOTA IN INDIAN ELECTIONS

The ineffectiveness of NOTA is evident from the results of various elections held in India since its introduction. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, NOTA polled over 1.1% of the total votes cast, with some constituencies recording NOTA votes exceeding 10%[5]. However, despite this significant number of NOTA votes, the election outcome remained unaffected. Similarly, in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, NOTA polled over 1.4% of the total votes cast, with some constituencies recording NOTA votes exceeding 20%. Again, the election outcome remained unaffected, with the second-highest candidate being declared the winner. The most significant event that happened in the Gujarat assembly elections was when the NOTA secured the third highest number of votes in 118 constituencies out of 182, which is almost 65% of the constituencies where NOTA secured the third highest vote bank. It was often described as “The silent kingmaker of Indian elections” and there were several posters that went viral on account of the slogan “Vote for NOTA”. Though having such a popularity amongst the voters the intended purpose of NOTA still feels unfulfilled.

THE REASONS BEHIND THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF NOTA

Several reasons contribute to the ineffectiveness of NOTA in Indian elections. One of the primary reasons is the lack of a clear alternative to voters. In the absence of a viable alternative, voters are forced to choose between subpar candidates, leading to a situation where the least undesirable candidate is elected. This is often referred to as the “lesser of two evils” syndrome. Voters are left with no choice but to choose a candidate who may not be their first preference, but is considered better than the other options. This lack of a clear alternative is due to various reasons, including the dominance of traditional parties, lack of new and innovative candidates, and the high cost of contesting elections. As a result, voters are left with limited options, making NOTA a less effective tool for expressing dissent. Another reason is the lack of awareness among voters about the NOTA option. In 2018, the Institute of Social and Economic Change (ISEC) conducted a study in the State of Karnataka on the General assembly elections, 2018. The study found that 55% of the voters in the State were unaware of the NOTA option or did not understand its implications.[6] This lack of awareness is a major concern, as it leads to a situation where NOTA votes are not cast effectively. Voters who are unaware of the NOTA option may end up casting their votes for a candidate who does not align with their values or preferences. Furthermore, voters who do not understand the implications of NOTA may not realize that it is a valid option for expressing dissent.

PERCEPTION OF NOTA AS A WASTED VOTE

Many voters perceive NOTA as a wasted vote because it does not directly contribute to the outcome of the election. In the current electoral system, a candidate can win an election even if they receive just one vote more than the other candidates. This means that even if a large number of voters opt for NOTA, it will not affect the outcome of the election. As former Chief Election Commissioner OP Rawat pointed out, “In an election, if 99 votes out of 100 go to NOTA and a candidate gets only one vote, still the candidate, and not NOTA, will be declared the winner.”[7] This highlights the limitations of the NOTA option in the current electoral system.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF NOTA’S INEFFECTIVENESS

The ineffectiveness of NOTA has significant implications for the democratic process in India. It undermines the trust of voters in the electoral process, leading to voter apathy and disillusionment. It also perpetuates the cycle of corrupt politics, as voters are forced to choose between subpar candidates. Furthermore, the ineffectiveness of NOTA raises questions about the accountability of elected representatives. If voters are unable to reject all candidates and demand fresh elections, it undermines the accountability of elected representatives to the people.

THE INDORE LOK SHABA ELECTIONS

The recent events in Indore’s Lok Sabha polls have exposed the dark underbelly of Indian democracy. The Congress party, deprived of a candidate due to the withdrawal of papers by its official nominee and rejection of papers of its substitute candidate, has been forced to appeal to voters to opt for the None of the Above (NOTA) option.[8] This unprecedented situation highlights the need for a more effective NOTA system, one that can truly empower voters and hold politicians accountable. Empowering NOTA can solve this crisis of democracy in several ways. Firstly, if a significant number of voters opt for NOTA, it should trigger a re-election, ensuring that the people’s voices are heard. Secondly, NOTA should be given legal consequences, such as the ability to reject all candidates and demand fresh elections. This would force political parties to field better candidates and be more accountable to the people. The Indore episode is a wake-up call for Indian democracy. It highlights the need for a more effective NOTA system, one that can truly empower voters and hold politicians accountable. By empowering NOTA, we can ensure that the people’s voices are heard, and that democracy is protected from those who seek to undermine it. It is time for the government to take concrete steps to strengthen the NOTA option, and give voters the power to demand better representation.

STRENGTHENING NOTA: REFORMS FOR A MORE EFFECTIVE TOOL FOR ELECTORAL REFORM

To address the limitations of NOTA, several reforms are necessary. One of the primary reforms is to introduce a system where in case the NOTA secured the highest vote bank then all the candidates nominated by the political parties in such constituency are deemed to be invalidated by the voters, making NOTA a distinct participant in the elections as if such vote bank has won the election. There needs a significant change in the electoral laws concerning NOTA. One possible solution is to make NOTA a binding option, where if more than 50% of voters opt for it, the election is cancelled and a fresh poll is conducted with new candidates[9]. In such an event, there should be a re-election in that constituency and all the candidates that are invalidated are ineligible to contest in that particular constituency in that course of election. This reform is to introduce a system of recall elections, where voters can recall their elected representatives if they fail to perform. This would provide an effective mechanism for voters to hold their elected representatives accountable.

As Anil Verma, head of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), suggested, “To take the NOTA option to the next level, it should be made legally powerful. We believe that if NOTA gets more votes than polled by the candidates in any seat, then the election should be cancelled and a fresh poll should be conducted with new candidates.”[10]

In order to truly make NOTA an effective tool for electoral reform, there needs to be a comprehensive overhaul of the existing legal framework governing elections in India. Provisions should be introduced that mandate a re-election or disqualification of candidates in case NOTA secures the highest number of votes in a constituency.[11] This would not only give voters a more meaningful way to express their dissatisfaction but also hold candidates accountable for their performance and conduct during the electoral process Efforts need to be made to increase awareness about the NOTA option and its implications. This can be done through voter education programs, media campaigns, and other initiatives. Efforts need to be made to promote NOTA as a valid option for expressing dissent. This can be done by highlighting the significance of NOTA and its potential to bring about change.

CONCLUSION

The introduction of NOTA in Indian elections was a significant reform, aimed at empowering voters and promoting electoral accountability. However, despite its promising beginnings, NOTA has failed to live up to its intended purpose. The limitations of NOTA, including its inability to influence election outcomes and provide a clear alternative to voters, have rendered it ineffective. To address these limitations, reforms such as proportional representation and recall elections are necessary. Until then, NOTA will remain a toothless tiger, unable to promote electoral accountability and clean politics in India. By strengthening the legal framework governing elections and empowering the NOTA option to have a more tangible impact on election results, India can move towards a more transparent and accountable electoral system.

[1] People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India (2013) 10 SCC 1

[2] INDIA CONST. art. 19 (1) (a)

[3] The Representation of People Act, 1951, § 62, No. 43, Acts of Parliament, 1951 (India).

[4] Law Comm’n of India, 255th Report: Electoral Reforms (2015).

[5] Deccan Herald, Lok Sabha Elections 2024 | Constituencies with the highest number of NOTA votes (July 31, 2024), https://www.deccanherald.com/elections/india/httpsadrindiaorgcontentanalysis-nota-votes-2013-2017-0-3049567.

[6] S.Madheswaran and B.P.Vani, Documentation and Evaluation of the SVEEP intervention General Assembly Election 2018, Karnataka, https://ceo.karnataka.gov.in/uploads/media_to_upload1636972727.pdf.

[7] OP Rawat, “NOTA could be effective only if more than 50 pc voters opt for it: Ex-CEC OP Rawat,” Economic Times, May 12, 2024, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/elections/lok-sabha/india/nota-could-be-effective-only-if-more-than-50-pc-voters-opt-for-it-ex-cec-op-rawat/articleshow/110055649.cms?from=mdr.

[8] “More than 2 lakh votes NOTA in Indore: Why NOTA was introduced, its consequences,” Indian Express, July 31, 2024, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/more-than-2-lakh-votes-nota-indore-9372026/.

[9] Ambrus, A., Greiner, B. and Zednik, A., 2019. The effects of a ‘None of the above’ballot paper option on voting behavior and election outcomes. Economic Research Initiatives at Duke (ERID) Working Paper, (277).

[10] Supra note 7

[11] Kumar, R., Padmanabhan, S. and Srikant, P., 2023. NOTA: a strategic choice with a positive impact on Indian elections. Asian Journal of Political Science, 31(3), pp.180-196.